Distinguishing Omphalocele and Gastroschisis

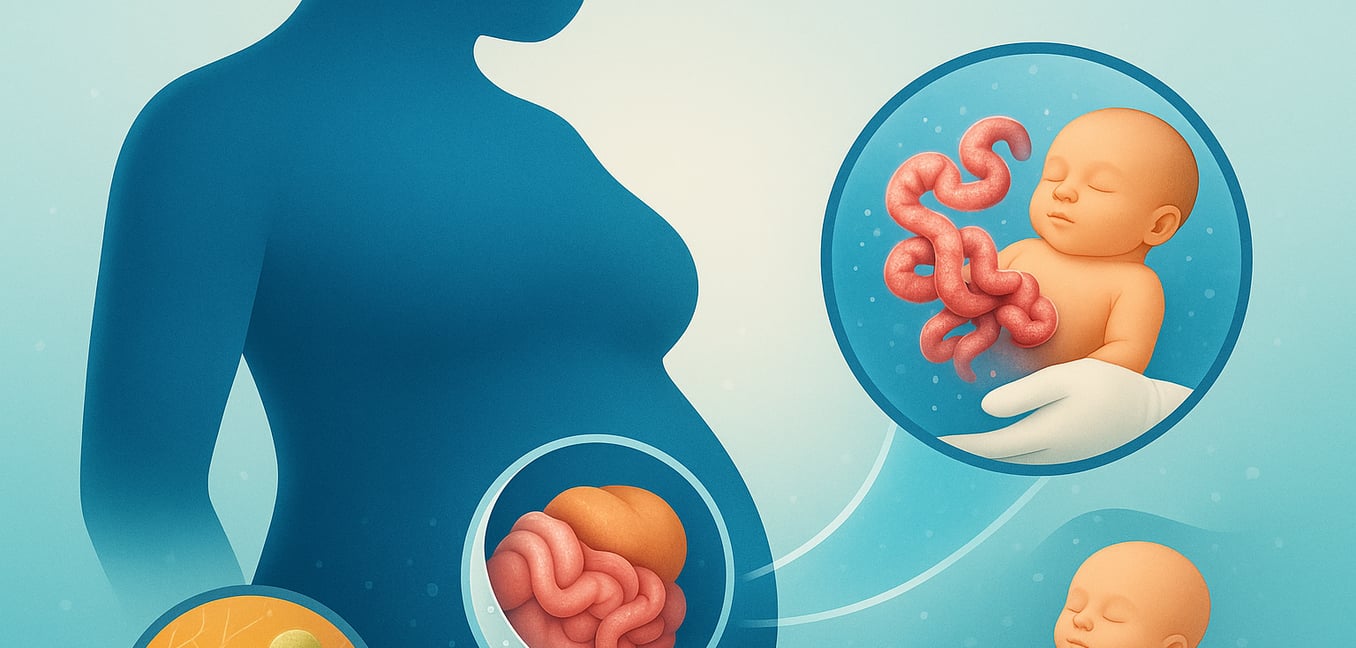

Congenital abdominal wall defects occur early in pregnancy when an infant’s abdominal wall fails to close completely, allowing internal organs to develop outside the body. The two most common types are omphalocele and gastroschisis. While both involve herniated organs and are often identified on prenatal ultrasounds, they are fundamentally different conditions. Understanding their distinctions in anatomy, underlying causes, and clinical management is crucial for grasping their unique challenges and treatment paths.

Anatomical Distinctions: The Core Differences

The most immediate way to differentiate these two conditions is by their physical appearance, specifically the location of the defect and whether the organs are covered by a protective sac. These anatomical features directly influence the prenatal environment of the organs and dictate the urgency of postnatal care.

Location and Protective Sac

- Omphalocele: The defect is located directly in the center of the abdomen at the navel. The umbilical cord inserts into a thin, membranous sac that encloses the protruding organs. This sac, made of peritoneum and amnion, shields the organs from direct contact with amniotic fluid.

- Gastroschisis: The defect is a small opening almost always found to the right of a normally inserted umbilical cord. Critically, there is no protective sac, leaving the intestines exposed to the irritant effects of amniotic fluid throughout gestation.

Herniated Organs

- Omphalocele: The contents can vary. Small defects may only contain intestines, but large or "giant" omphaloceles often include the liver and other abdominal organs. The presence of the liver outside the abdomen is a key diagnostic sign of an omphalocele.

- Gastroschisis: The herniation typically involves only the small and large intestines, which float freely in the amniotic fluid. This prolonged exposure often causes the bowel to become inflamed, thickened, and covered in a layer of inflammatory material.

Underlying Causes and Risk Factors

Beyond the physical anatomy, omphalocele and gastroschisis have starkly different connections to other health issues, genetic factors, and maternal risk profiles. This points to very different developmental origins for the two conditions.

Associated Conditions and Genetics

Omphalocele is frequently part of a broader clinical picture. Between 30% and 70% of infants with an omphalocele have a chromosomal abnormality, such as trisomy 13, 18, or 21. It is also a feature of genetic syndromes like Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. Consequently, a prenatal diagnosis of omphalocele prompts further testing, including amniocentesis and a detailed fetal echocardiogram to check for heart defects.

In sharp contrast, gastroschisis is usually an isolated defect. It is rarely associated with chromosomal abnormalities or other major congenital anomalies. While intestinal complications like blockages can occur, these are considered a direct result of the defect itself, not separate, unrelated issues.

Maternal Risk Factors and Incidence Trends

The demographic patterns for these conditions are also distinct. Gastroschisis is strongly associated with young maternal age, most often occurring in mothers younger than 25, particularly during a first pregnancy. This suggests that environmental or nutritional factors may play a role. Furthermore, the global incidence of gastroschisis has risen dramatically over the past few decades, a trend that points away from purely genetic causes.

Omphalocele, however, is more commonly linked to the extremes of maternal reproductive age, especially advanced maternal age (over 40). This aligns with the increased risk of chromosomal abnormalities in older mothers. Unlike gastroschisis, the incidence of omphalocele has remained relatively stable over time, supporting the theory that its causes are more tied to intrinsic genetic or developmental events.

Clinical Management: From Diagnosis to Repair

The management approach for each defect is tailored to its unique characteristics, from the moment of birth through surgical repair. The primary goals are to protect the exposed organs, maintain the infant's stability, and safely return the organs to the abdominal cavity.

Initial Stabilization

Immediately after birth, the first steps are the same for both conditions. The exposed organs are covered with a sterile dressing or a "bowel bag" to prevent heat and fluid loss and to protect against infection. The infant is placed in an incubator, and intravenous (IV) fluids are started. A nasogastric tube is inserted to decompress the stomach and bowel, which prevents further swelling and makes surgical repair easier.

Surgical Approaches

The timing and method of surgical repair differ significantly based on the diagnosis.

- Gastroschisis: Surgery is urgent. Due to the inflammation of the unprotected bowel, surgeons aim to return the intestines to the abdomen soon after birth. If the bowel is not too swollen, a primary repair may be done in one operation. More often, a staged repair is performed using a device called a silo. This plastic pouch is placed over the intestines and suspended, allowing gravity to gently guide the organs back into the abdomen over several days as swelling subsides.

- Omphalocele: The approach is more varied and often less urgent, especially if the protective sac is intact. For small defects, a primary surgical closure may be performed. For giant omphaloceles where the abdominal cavity is too small, a non-operative "paint and wait" strategy may be used. This involves applying topical agents to the sac, allowing skin to gradually grow over it, creating a large hernia that can be repaired later in childhood. A staged silo closure can also be used for large omphaloceles if the sac has ruptured or if a surgical approach is preferred.