Long-Term Care for Children with Congenital Toxoplasmosis

Congenital toxoplasmosis occurs when the Toxoplasma gondii parasite is passed from a mother to her unborn child during pregnancy. While the mother often has no symptoms, the infection can have serious consequences for the baby. Effective care involves a clear path from diagnosis to initial treatment and, most importantly, a dedicated plan for lifelong monitoring to protect the child’s health and development.

A Path to Diagnosis: From Pregnancy to Birth

Identifying congenital toxoplasmosis involves a series of steps that begin during pregnancy and continue after the baby is born. The goal is to confirm the infection and understand its potential impact as early as possible.

The process often starts with a routine blood test for the mother during a prenatal visit. This screening looks for antibodies (IgG and IgM) that show whether an infection is recent or occurred in the past. If a recent infection is suspected, an IgG avidity test can help clarify the timing. Low-avidity antibodies suggest the infection happened recently, increasing the risk of transmission to the fetus.

If a recent maternal infection is confirmed, an amniocentesis may be offered after 18 weeks of gestation. This test analyzes a small sample of amniotic fluid for the parasite’s DNA using a highly sensitive technique called polymerase chain reaction (PCR). A positive PCR confirms the fetus is infected and helps guide treatment decisions.

After birth, a comprehensive evaluation is performed on the newborn to confirm the diagnosis and check for any signs of the disease. This initial assessment creates a crucial baseline for all future care and includes several key tests:

- Specialized Blood Tests: A newborn’s blood is tested for IgM or IgA antibodies. Since these antibodies do not cross the placenta from the mother, their presence indicates the baby’s own immune system is fighting the infection.

- Brain Imaging: To check for effects on the brain, doctors use imaging like a head ultrasound, CT scan, or MRI. These scans look for signs such as fluid buildup (hydrocephalus) or small calcium deposits (intracranial calcifications).

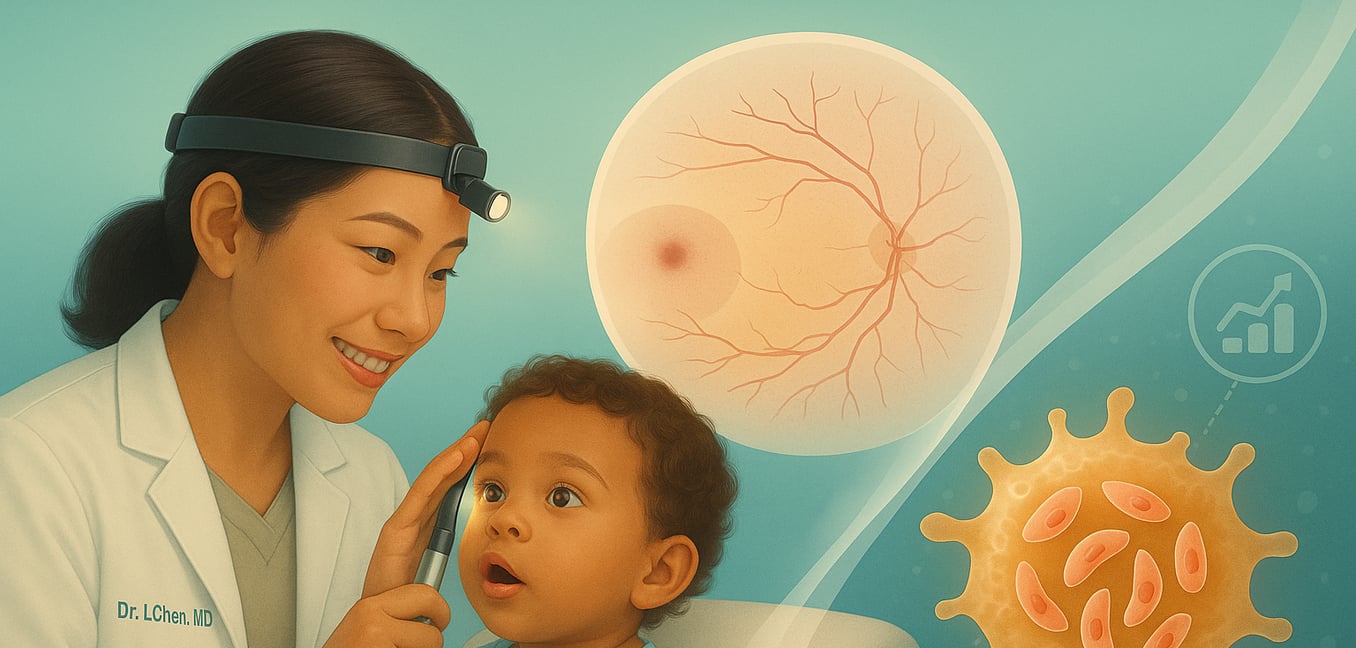

- Eye Examination: A pediatric ophthalmologist performs a detailed eye exam to look for chorioretinitis, which is inflammation and scarring on the retina. This condition is a classic sign of congenital toxoplasmosis and can severely impair vision.

- Spinal Tap (Lumbar Puncture): A small sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is collected from the baby’s lower back. The fluid is checked for signs of inflammation and tested with PCR to see if the parasite is present in the central nervous system.

The First Year: Initial Treatment and Monitoring

Once congenital toxoplasmosis is diagnosed, treatment begins immediately to fight the parasite and reduce the risk of long-term damage, especially to the brain and eyes. This therapy is a long-term commitment, typically lasting for one full year.

The standard treatment combines two drugs, pyrimethamine and sulfadiazine, which work together to stop the parasite from multiplying. However, pyrimethamine can lower a baby's blood cell counts, which can lead to anemia or make them more vulnerable to infections. To prevent this, a special form of B-vitamin called folinic acid (or leucovorin) is always given alongside it. This supplement protects the baby from the side effect without stopping the main drugs from working.

In cases where there is severe inflammation in the brain or eyes, doctors may temporarily add a corticosteroid, like prednisone, to the treatment plan. Steroids do not kill the parasite but are powerful anti-inflammatory medicines that reduce swelling and prevent further tissue damage. They are used for a short time and then carefully tapered off.

Throughout the year of treatment, the infant is monitored closely for side effects. Regular blood tests, often weekly at first, are done to check the baby’s blood cell counts. If the counts drop too low, the dose of folinic acid may be increased or treatment may be briefly paused to allow the body to recover, ensuring the therapy is both safe and effective.

Lifelong Follow-Up: Preventing Late Complications

Completing the first year of treatment is a major milestone, but it is not the end of care. The Toxoplasma parasite can remain in the body in a dormant, cyst form for life. These cysts can reactivate years later, causing new problems or a flare-up of old ones. For this reason, long-term follow-up is essential to catch any late-onset complications early.

Protecting Vision with Regular Eye Exams

Lifelong eye care is the most critical part of follow-up. The primary concern is chorioretinitis, which can cause new inflammation or reactivate old scars on the retina, leading to permanent vision loss. A pediatric ophthalmologist will monitor for this with regular exams, typically scheduled every few months for the first few years of life and at least annually after that.

The goals of these check-ups are to:

- Detect new inflammation or reactivation of old scars early.

- Intervene quickly with another course of treatment to prevent vision damage.

- Monitor for any vision changes, especially if lesions are near critical parts of the retina like the macula or optic nerve.

Monitoring Development and Neurological Health

Ongoing developmental assessments are key to ensuring the child is meeting their milestones. Even with successful treatment, some children may experience learning, behavioral, or motor skill challenges that become more apparent as they grow.

Regular visits with a pediatrician or a neurodevelopmental specialist help track cognitive function, coordination, and overall progress. This continuous monitoring is vital for identifying conditions like learning disabilities, attention deficits, or even late-onset seizures. Early identification allows for timely support through specialized therapies, educational resources, or medical management, giving the child the best chance to thrive in school and beyond.

Ensuring Hearing with Routine Screenings

Congenital toxoplasmosis can cause delayed or progressive hearing loss that may not be present at birth. A child might pass their newborn hearing screen but develop problems later. Therefore, routine auditory evaluations are a standard part of the long-term care plan, usually recommended every year throughout early childhood.

These tests can detect subtle changes in hearing that might otherwise go unnoticed but could significantly impact a child’s speech and language development. Catching any hearing impairment early allows for prompt intervention with tools like hearing aids or access to specialized educational support, which is crucial for academic and social success.