Understanding Glutaryl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency

Glutaryl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency (GA-I), also known as Glutaric Acidemia Type I, is an inherited metabolic disorder. It affects the body's capacity to properly break down certain amino acids—L-lysine, L-hydroxylysine, and L-tryptophan. These amino acids are fundamental components of proteins. The condition follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, meaning a child must inherit a defective gene from both parents to manifest the disorder.

Key characteristics of Glutaryl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency include:

- Genetic Roots: GA-I results from inherited mutations in the GCDH gene. This gene provides the instructions for making an enzyme called glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase. When this enzyme is deficient or non-functional due to these mutations, the body cannot effectively break down L-lysine, L-hydroxylysine, and L-tryptophan.

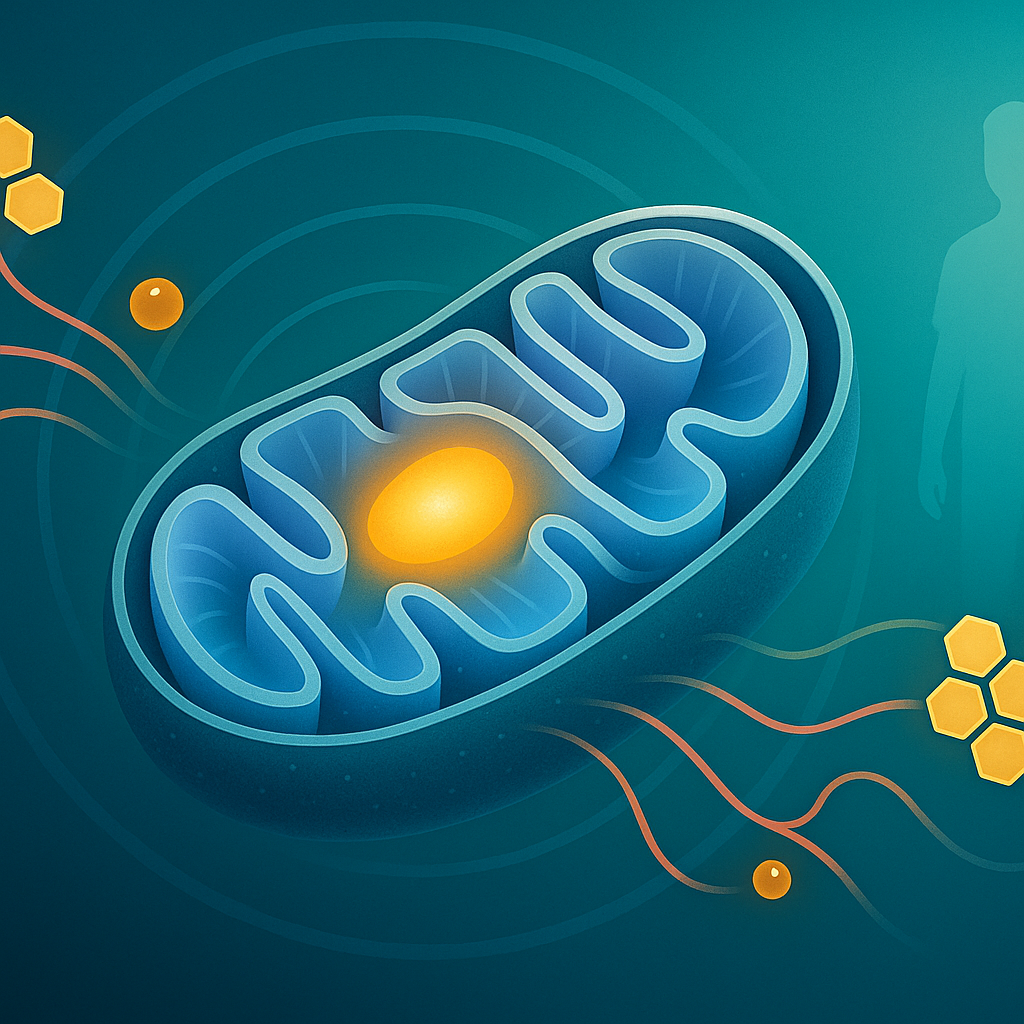

- Metabolic Disruption: The GCDH enzyme is crucial for a specific step in processing these amino acids. Its absence blocks this pathway, leading to the accumulation of harmful substances like glutaric acid (GA) and 3-hydroxyglutaric acid (3-OH-GA), particularly within the brain. This buildup is toxic and can interfere with brain cell energy and function.

- Variable Clinical Picture: Symptoms can differ greatly among individuals. While some infants may seem normal at first, an enlarged head (macrocephaly) is a common early physical sign. A significant concern is the risk of sudden, severe episodes of brain dysfunction, known as encephalopathic crises, especially in early childhood. These crises can lead to permanent neurological damage.

- Carnitine Depletion: The accumulation of glutaric acid often leads to a secondary shortage of carnitine. Carnitine is vital for transporting fatty acids into mitochondria for energy production. In GA-I, glutaric acid binds to carnitine, forming glutarylcarnitine, which is then excreted in urine. This loss depletes carnitine stores, further impairing energy production and potentially worsening muscle-related symptoms.

Early Indicator: Macrocephaly

One of the first noticeable physical signs in infants with Glutaryl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency can be macrocephaly, an unusually large head. Recognizing this symptom is important for early diagnosis, as it may appear before more severe neurological issues develop.

- Common in Early Infancy: Approximately 75% of babies with GA-I exhibit macrocephaly, often noticeable at birth or shortly thereafter. This makes routine head circumference measurements during well-baby checkups a valuable tool for early detection.

- Signal for Further Investigation: An infant with an unexplained enlarged head should be evaluated for underlying conditions like GA-I. Early identification through biochemical screening can lead to prompt diagnosis and proactive management, potentially preventing or mitigating severe neurological damage.

- Associated Brain Characteristics: In GA-I, macrocephaly is often linked to specific findings on brain MRI scans. These can include unusually wide spaces for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), particularly around the temporal lobes and within the Sylvian fissures (natural grooves on the brain's surface). These imaging clues may be present even before other neurological symptoms manifest.

- Distinguishing from Benign Causes: While a larger head can be a harmless family trait, macrocephaly associated with GA-I signals a serious metabolic disorder. If an infant's head is unusually large, grows rapidly, or is accompanied by subtle developmental delays or low muscle tone, a comprehensive medical evaluation is essential to differentiate it from benign causes and ensure timely care.

Neurological Manifestations and Developmental Concerns

Beyond macrocephaly, Glutaryl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency can lead to a spectrum of neurological challenges and developmental issues. These problems often, though not exclusively, emerge following a severe metabolic event known as an encephalopathic crisis (detailed in the subsequent section). The impact on brain function and development includes:

- Movement Disorders: Significant difficulties with movement are a common consequence. Dystonia, characterized by involuntary muscle contractions that cause twisting, repetitive movements, or abnormal postures, is frequently observed. Other movement problems can include muscle spasms, slow, writhing movements, stiff muscles (rigidity), or, conversely, weak, floppy muscles (hypotonia), all of which can severely hinder daily activities like sitting, feeding, and purposeful actions.

- Developmental Delays: Neurological injury, particularly to the brain's basal ganglia, often results in delays in achieving key developmental milestones. Children may be slow to develop motor skills such as rolling over, sitting up, crawling, or walking. Cognitive development can also be impacted, with the severity varying among individuals; effects may be more pronounced if severe crises occur early in life, sometimes leading to intellectual disability.

- Gradual Onset of Neurological Issues: While acute crises are dramatic, some individuals with GA-I may experience a more insidious, or gradual, onset of neurological symptoms. In these cases, brain injury and resulting disabilities might develop slowly over time without a clearly identifiable crisis. These children might exhibit progressive motor delays, difficulties with fine motor skills, or subtle neurological signs that worsen before diagnosis, indicating that damage can occur even without a distinct, severe illness.

Acute Encephalopathic Crises: A Critical Complication

Acute encephalopathic crises represent extremely serious events for children with undiagnosed or inadequately managed Glutaryl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency. These sudden episodes of severe brain dysfunction can lead to permanent neurological damage.

- Vulnerable Age and Common Triggers: These crises most often occur in young children, typically between 3 months and 3 years of age, although there is a smaller risk up to age 6. Crises are generally not reported beyond this age. They are frequently triggered by events that put the body under metabolic stress, such as febrile illnesses (especially gastroenteritis, which can lead to poor food intake and dehydration), febrile reactions to vaccinations, or periods of fasting (e.g., before surgery).

- Mechanism of Brain Injury: During an encephalopathic crisis, there is a rapid accumulation of glutaric acid and 3-hydroxyglutaric acid in the brain. This severely disrupts cerebral energy metabolism. The striatum, a brain region critical for controlling movement, is particularly vulnerable to this toxic insult, often resulting in irreversible damage. This targeted injury to striatal neurons is the primary cause of the severe motor disabilities observed after such events.

- Recognizing Warning Signs of a Crisis: The clinical signs of an impending or ongoing crisis can escalate rapidly and demand immediate medical attention. Parents and caregivers should be vigilant for symptoms such as a sudden decrease in alertness or pronounced lethargy, persistent vomiting, increased irritability, a noticeable loss of muscle tone (hypotonia or floppiness), or the new onset of abnormal movements like dystonia. In severe cases, the child may progress to a coma.

- Long-term Neurological Consequences: The irreversible damage to the striatum sustained during an encephalopathic crisis typically leads to a complex and often severe movement disorder. Dystonia, involving involuntary muscle contractions that cause twisting movements or abnormal postures, is a prominent outcome. This profoundly affects voluntary actions, impacting abilities like feeding, speaking, and mobility, often resulting in significant long-term disability and reliance on supportive care.

Other Notable Symptoms and Clinical Variability

The presentation of Glutaryl-CoA Dehydrogenase Deficiency can vary significantly from one person to another. Beyond the commonly discussed neurological issues, other symptoms and patterns are important for a complete understanding.

- Asymptomatic or Mildly Affected Individuals: Some individuals with the genetic predisposition for GA-I may never develop noticeable symptoms or may only experience very mild ones. This is particularly true if they manage to avoid significant metabolic stressors. Such cases underscore the variability of the disorder and can be challenging to identify without newborn screening programs or a known family history.

- Biochemical Differences and Clinical Risk: Individuals with GA-I can be categorized biochemically based on the levels of specific metabolites in their urine (e.g., "low" or "high" excreters of glutaric acid). However, this biochemical distinction does not consistently predict the clinical severity of the condition. Even "low excreters" remain at significant risk for brain injury during an encephalopathic crisis, necessitating careful, proactive management for all diagnosed individuals.

- Late-Onset Forms: While GA-I often presents dramatically in infancy, some individuals may not show clear signs until later in childhood, adolescence, or even adulthood. These late-onset presentations might involve more non-specific neurological symptoms such as persistent headaches, vertigo (dizziness), or difficulties with fine motor skills, rather than acute crises. These cases may not always involve the typical striatal injury seen in early-onset forms.

- Bleeding Abnormalities: In some serious instances, particularly during or following an acute crisis, children with GA-I can develop bleeding within the brain (subdural hematomas) or eyes (retinal hemorrhages). This is a critical point because such findings can be tragically misattributed to non-accidental injury if GA-I is not considered as an underlying cause. Awareness of this possibility is vital when such bleeding accompanies neurological changes in a young child.

- Broader Metabolic Disturbances During Illness: During periods of illness or metabolic stress, individuals with GA-I can experience widespread metabolic imbalances beyond direct neurological concerns. These may include a dangerous build-up of acid in the blood (metabolic acidosis), high levels of substances called ketones (ketosis), and sometimes elevated ammonia levels (hyperammonemia) or abnormal liver function tests. These systemic issues further complicate the clinical picture and require urgent medical intervention.