Can You Be Short and Have Marfan Syndrome?

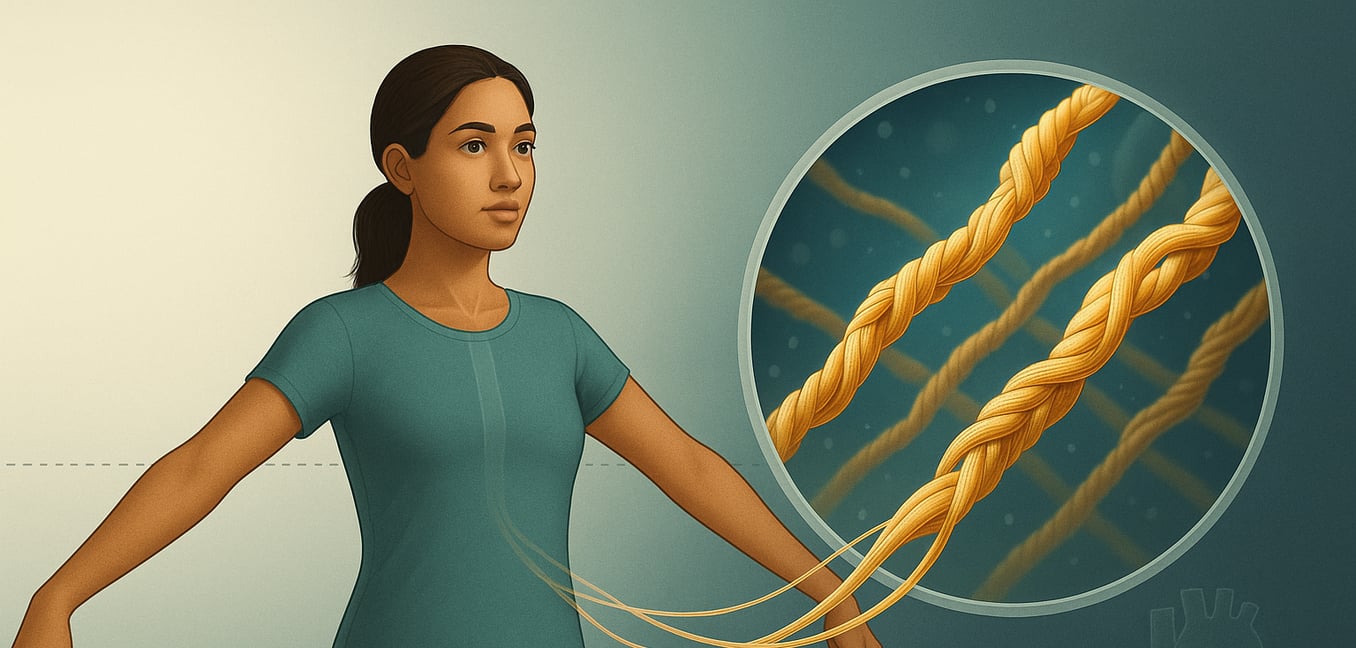

Marfan syndrome is a genetic disorder that impacts the body's connective tissue—the material that acts as a scaffold for organs, bones, and blood vessels. The condition is caused by a mutation in the FBN1 gene, which provides the blueprint for a protein called fibrillin-1. This protein is crucial for giving connective tissue its strength and elasticity. Without enough functional fibrillin-1, tissues throughout the body become weak and prone to stretching.

This genetic flaw is typically passed down from a parent with the condition. Following an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, a child of an affected parent has a 50% chance of inheriting the disorder. However, in about 25% of cases, Marfan syndrome results from a new, spontaneous mutation in the FBN1 gene in a person with no family history of the disorder.

The Common Misconception: The Tall, Slender Body

The most recognizable image associated with Marfan syndrome is that of an exceptionally tall, thin individual. This physical appearance, known as a marfanoid habitus, is a classic sign and often the first clue that leads to a diagnosis. It occurs because the defective fibrillin-1 protein allows the body's long bones to grow more than they normally would.

This stereotype is characterized by several distinct features:

- Significant Height: Individuals are often much taller than their family members, with a lean build and little body fat.

- Disproportionately Long Limbs: A key indicator is an arm span that is greater than the person's height. This disproportion, called dolichostenomelia, is a more specific sign than height alone.

- Long Fingers and Toes: Known medically as arachnodactyly, or "spider fingers," this can be checked with simple clinical tests like the "thumb sign" and "wrist sign," which demonstrate the combination of long digits and slender wrists.

- Distinct Facial Features: A long, narrow face, a high-arched palate leading to crowded teeth, and a small or receding jaw are also common.

The Reality: Marfan Syndrome Without Exceptional Height

While the tall stereotype is well-known, it is a significant misconception that everyone with Marfan syndrome is tall. The disorder's effects vary dramatically from person to person, and an individual can have the condition while being of average or even short stature. Height is just one piece of a much larger and more complex diagnostic puzzle.

Genetic Variability

The FBN1 gene mutation has what is known as "variable expressivity," meaning it can manifest in countless different ways, even within the same family. Just as one person may have severe heart problems while a relative has only mild eye issues, the effect on skeletal growth is not uniform. An individual can carry the gene mutation but not experience the significant bone overgrowth that leads to a tall stature. They may have a completely average height while still facing the more dangerous, invisible complications of the syndrome, such as an enlarging aorta.

The Influence of Family Genetics

A person's underlying genetic blueprint for height, inherited from their family, plays a crucial role. If someone comes from a family that is genetically predisposed to being short, having Marfan syndrome might make them taller than their relatives but not necessarily "tall" compared to the general population. Their final height could easily fall within the average range. In these cases, other physical signs—like a long arm span, arachnodactyly, or a curved spine—become far more important clues for diagnosis than height alone.

Impact of Skeletal Complications

Other skeletal problems common in Marfan syndrome can directly reduce a person's measured height. Severe scoliosis (a sideways curvature of the spine) or kyphosis (a forward rounding of the back) are frequent complications that can cause a significant loss of stature. This can make an individual appear much shorter than their limbs would suggest. Therefore, even if someone has the characteristically long arms and legs, their overall standing height might be masked by the structural impact of a curved spine or other postural changes.

Diagnosis Is More Than Just Height

Because physical signs like stature can be misleading, diagnosing Marfan syndrome requires a comprehensive evaluation by a team of medical specialists. Physicians cannot rely on a single characteristic; instead, they act as detectives, gathering clues from different body systems to build a complete clinical picture.

Cardiovascular Evaluation

The most critical part of the diagnostic process involves assessing the heart and aorta due to the risk of life-threatening complications. The primary tool is an echocardiogram, an ultrasound that creates images of the heart. This test allows doctors to precisely measure the aorta to check for an aneurysm (a bulge) and examine the heart valves, particularly the mitral valve, for weakness or leakage. These findings are major criteria for a diagnosis.

Ocular Examination

A detailed eye exam by an ophthalmologist is essential, as certain eye problems are highly specific to Marfan syndrome. The most important test is a slit-lamp exam, performed after the pupils are dilated. This allows the doctor to look for ectopia lentis—a dislocation of the eye's lens—which is a hallmark sign of the condition. The exam also screens for an increased risk of retinal detachment, glaucoma, and early-onset cataracts.

Genetic Testing

When physical signs are unclear or a family history is present, genetic testing can provide a definitive answer. A blood test can identify a mutation in the FBN1 gene, confirming the diagnosis. This is especially valuable for family members, as it can determine if they have inherited the gene even with few or no symptoms, allowing for proactive monitoring and life-saving care. However, a negative test does not completely rule out the condition, as not all causative mutations are known.