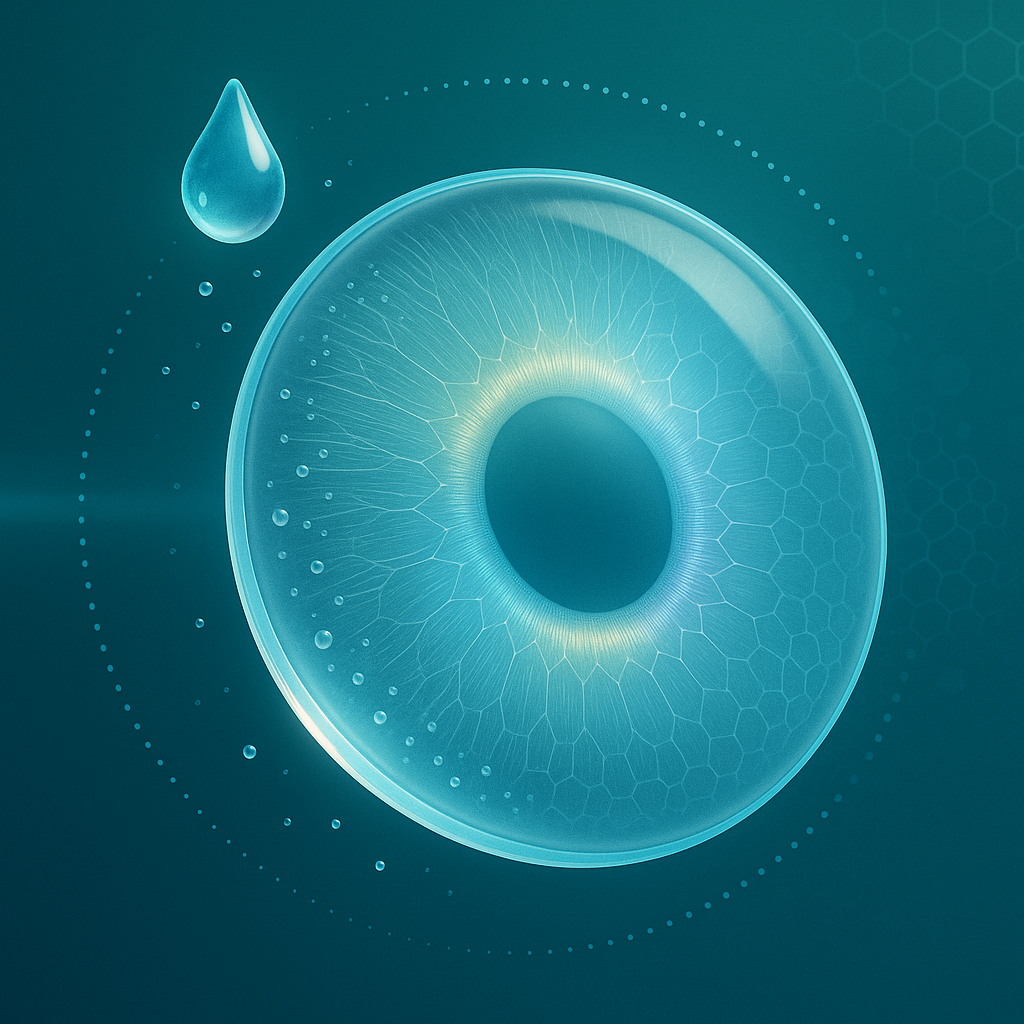

Corneal dystrophy is an umbrella term for a group of over 20 different eye diseases, all of which have a genetic basis. This means the conditions are caused by changes, or mutations, within a person's DNA that disrupt the normal development and function of the cornea. These genetic instructions are responsible for building and maintaining the cornea's clear, structured layers; when flawed, they can lead to the buildup of abnormal material or structural weaknesses that impair vision. These genetic alterations can be passed down through families, inherited from one or both biological parents, but they can also occur spontaneously in an individual with no prior family history of the disease. While a family history is the single most significant risk factor, the exact genetic underpinnings for some dystrophies are still being uncovered by researchers.

The way these genetic changes are passed down varies, which influences how the conditions appear in families. Many types, including the most common form, Fuchs endothelial corneal dystrophy, as well as epithelial basement membrane dystrophy and several stromal dystrophies, follow an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. In these cases, inheriting just one copy of the mutated gene from a single parent is enough to cause the disorder, giving a child a 50 percent chance of also inheriting the condition if one parent is affected. Other dystrophies are autosomal recessive, meaning a person must inherit a copy of the mutated gene from both biological parents to develop the disease. People who carry only one copy of a recessive gene are typically unaffected carriers. Examples of recessive conditions include macular corneal dystrophy and a form of congenital hereditary corneal edema (CHED type 2). A few dystrophies may even be X-linked, meaning the mutation is carried on the X chromosome and affects males and females differently.

Scientific breakthroughs, particularly since the 1990s, have dramatically improved our understanding of the specific genes involved. A significant number of autosomal dominant stromal dystrophies, such as Granular, Lattice, and Reis-Bückler’s dystrophy, have been linked to mutations on the 5q31 chromosome, specifically within a single gene called TGFBI. Other genes, like KRT3 and KRT12, are associated with epithelial dystrophies such as Meesmann dystrophy. Researchers continue to identify new genetic links across various chromosomes, including 1p32, 16q22, and 20p11.2, each tied to different forms of dystrophy. This ongoing research is crucial because it helps to precisely define these conditions, distinguishing them from other corneal problems that are not hereditary, such as keratoconus, or issues related to systemic diseases. Because symptoms can be subtle or appear later in life, a definitive genetic diagnosis can help clarify the condition for patients and their families, even when a family history was previously unknown.

What is the age of onset for corneal dystrophy?

The age at which corneal dystrophy first appears can vary widely depending on the specific type of the disorder. Some forms, such as classic Lattice Corneal Dystrophy (Type I), may begin to show symptoms as early as the first or second decade of life. In contrast, other types have a much later onset; for instance, Anterior Basement Membrane Dystrophy—the most common corneal dystrophy—typically presents anytime between 25 and 75 years of age. Certain variants may not become apparent until even later in life, sometimes after the seventh decade. Therefore, while some individuals can develop symptoms in childhood or adolescence, it is also very common for the condition to emerge in middle age or later, highlighting the broad spectrum of onset across different dystrophies.

Can glasses help with corneal dystrophy?

While glasses can correct common vision problems, their effectiveness for corneal dystrophy is often limited. In the very early stages of the condition, glasses may help improve vision if the dystrophy has not yet caused significant irregularities on the corneal surface. However, as the condition progresses, the cornea becomes uneven, leading to visual distortions and blurriness that glasses cannot fix. Because glasses sit in front of the eye, they are unable to create the smooth, regular optical surface needed to properly focus light through a distorted cornea. Therefore, while they might offer minimal benefit initially, they are not considered a primary or long-term solution for the complex visual challenges posed by most corneal dystrophies, which is why specialized treatments like scleral lenses are often recommended.

Is corneal dystrophy a disability?

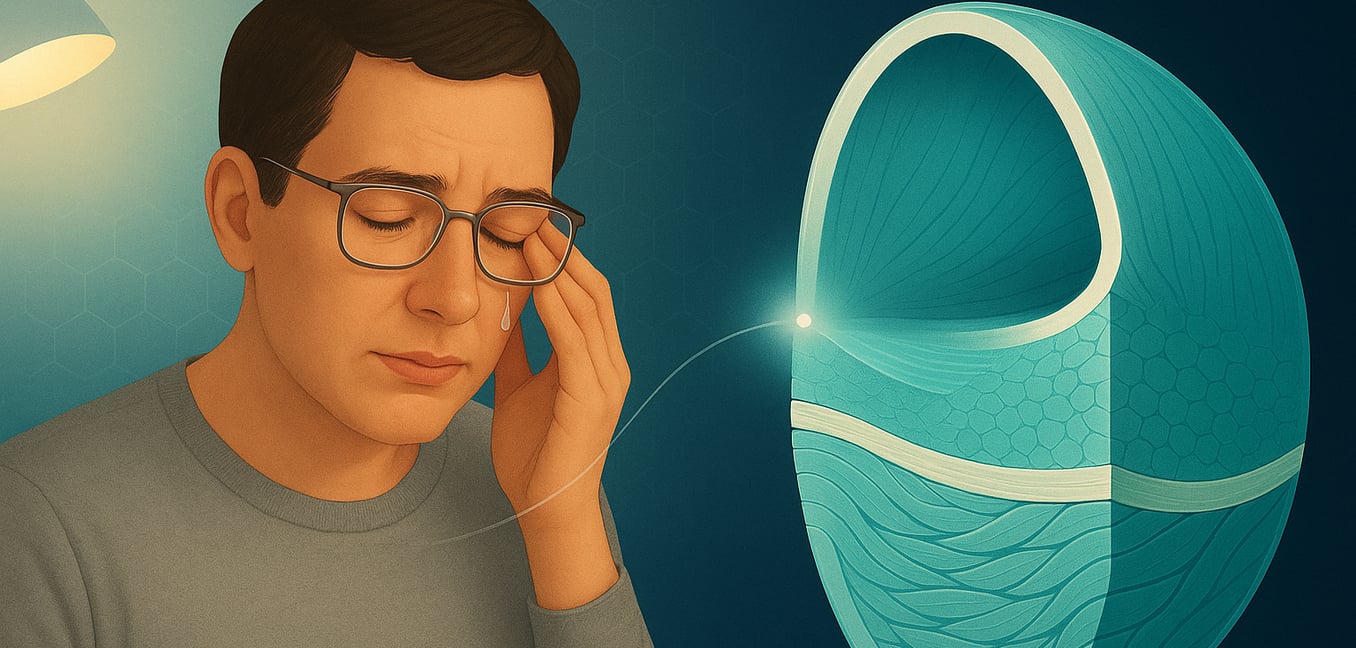

Corneal dystrophy can be considered a disability, especially when it leads to significant visual impairment that affects a person's daily life. Many people in the early stages of the condition may be asymptomatic or experience only minor eye discomfort. However, as the disease worsens, symptoms such as severe blurriness, vision loss, light sensitivity, or chronic pain from recurrent corneal erosions can become more pronounced. When these issues substantially limit a person's ability to perform essential tasks like reading, driving, or working, corneal dystrophy may qualify as a disability.

What eye drops are good for corneal dystrophy?

Several types of eye drops can help manage the symptoms of corneal dystrophy, although they do not treat the underlying condition. For specific types like Fuchs dystrophy, where the cornea swells with fluid, an eye care professional may recommend saline (5% sodium chloride) eye drops or ointments to help draw out excess fluid, reduce swelling, and temporarily improve cloudy vision. To relieve the gritty or dry sensation associated with some dystrophies, preservative-free lubricating eye drops are often used. During painful flare-ups from recurrent corneal erosions, antibiotic eye drops may also be prescribed to prevent infection. Researchers are also actively developing new therapeutic eye drops, such as those containing the antioxidant ubiquinol, which aim to directly target the disease process and may offer more advanced treatment options in the future.

What is difference between corneal dystrophy and degeneration?

Clinicians must distinguish between corneal dystrophy and corneal degeneration, as they have different origins. Corneal dystrophy is a genetic disorder, meaning it is typically inherited and often presents symmetrically in both eyes without being linked to external factors. These conditions have a higher tendency to affect a person's vision. In contrast, corneal degeneration is an acquired condition that damages the cornea's structure due to factors like aging, trauma, infection, or other environmental issues. Unlike dystrophies, degenerations are not caused by a person's genes and can develop at any point in life, sometimes affecting only one eye.

What happens if dry eyes are left untreated?

Leaving dry eye syndrome untreated goes beyond simple discomfort, potentially leading to serious eye health complications and a decreased quality of life. Without the protective lubrication of tears, your eyes are more susceptible to infections like conjunctivitis and damage from everyday debris. This can escalate to more severe conditions such as keratitis (corneal inflammation) or painful corneal ulcers, which carry the risk of permanent scarring and even vision loss. Over time, persistent symptoms like blurred vision, extreme light sensitivity, and a gritty sensation can make daily activities like reading, driving, or wearing contact lenses incredibly challenging and uncomfortable.

Can corneal erosion cause blindness?

While permanent blindness from recurrent corneal erosion (RCE) is uncommon, the condition can cause significant, albeit often temporary, vision disturbances. During an acute episode, the severe pain and extreme sensitivity to light (photophobia) can be so debilitating that patients experience a form of functional blindness, as they are unable to keep their eyes open. The primary risk for long-term vision impairment stems from complications. Repeated damage from RCEs can lead to corneal haze or scarring, which clouds the normally clear tissue and obstructs light from entering the eye. Additionally, the damaged corneal surface increases the risk of a serious infection, which could potentially result in permanent scarring and vision loss if not treated effectively.