Understanding Corneal Dystrophy

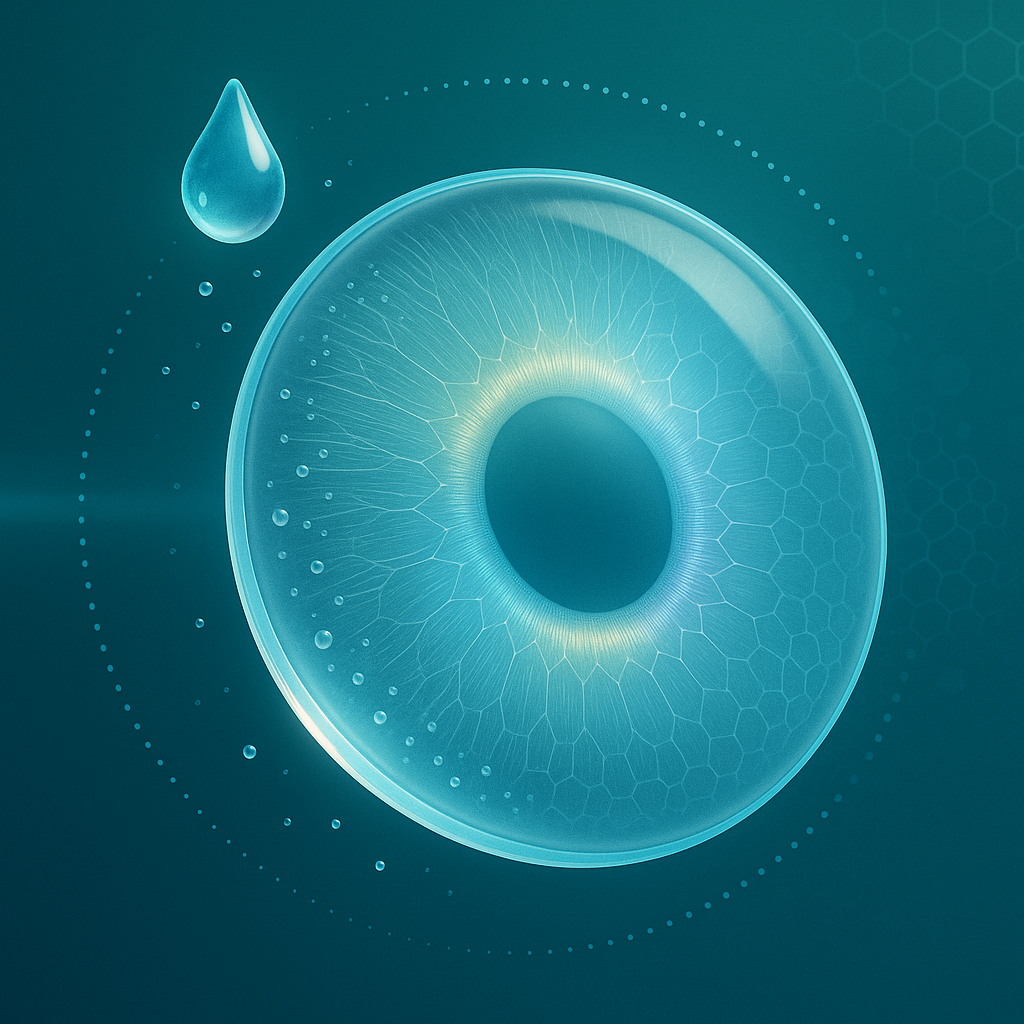

Corneal dystrophies are a group of inherited conditions that cause the cornea—the clear front window of the eye—to become cloudy, leading to vision loss. The most common type is Fuchs’ endothelial corneal dystrophy (FECD), a progressive disease that primarily affects the cornea's innermost layer, the endothelium.

The endothelium is a single layer of cells that acts as a pump, constantly removing fluid to keep the cornea transparent. In Fuchs’ dystrophy, these vital cells gradually die off, and the body cannot replace them. As the cell count drops, the pump system fails, and fluid accumulates in the cornea, causing it to swell. This swelling, known as corneal edema, is the primary reason vision becomes blurry and hazy. A key sign of the disease is the formation of tiny, wart-like bumps called guttae on the membrane beneath the endothelium.

As the disease advances, the chronic swelling can lead to painful, fluid-filled blisters forming on the cornea's surface, which can rupture and cause significant discomfort. Over time, this may lead to permanent scarring that can impair vision even if the underlying swelling is treated with a transplant.

The Modern Gold Standard: Endothelial Keratoplasty

For patients whose vision is significantly impaired by corneal swelling, the treatment landscape has been transformed by a surgical procedure called endothelial keratoplasty. This partial-thickness transplant targets only the diseased endothelial layer, representing a major leap forward from traditional full-thickness transplants that replaced the entire cornea.

The most refined version of this surgery is Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK). During a DMEK procedure, the surgeon carefully removes the patient’s damaged endothelium and replaces it with an incredibly thin layer of healthy donor cells. The advantages are substantial. Because the procedure uses a small, self-sealing incision without sutures, patients experience faster healing, no surgically induced astigmatism, and a lower risk of infection or wound rupture compared to older techniques.

While DMEK offers remarkable results, it still relies on a limited supply of human donor tissue. This dependency is the primary driver behind the search for next-generation experimental therapies that could one day make donor tissue unnecessary.

Regenerative Medicine: Using Stem Cells for Repair

To overcome the challenge of donor tissue shortages, researchers are exploring a highly personalized approach: using a patient's own stem cells to regenerate a healthy cornea. This field of regenerative medicine aims to unlock the body's inherent healing capabilities to repair damage at a cellular level.

A pioneering procedure known as CALEC (cultivated autologous limbal epithelial cells) exemplifies this cutting-edge technique. It involves taking a small biopsy of stem cells from the patient’s healthy eye. These cells are then grown and expanded in a specialized lab over several weeks to form a new sheet of tissue. This custom-grown graft is then transplanted into the damaged eye, where it works to restore the corneal surface.

An early human trial, the first of its kind funded by the National Eye Institute, produced highly encouraging results. The study found the treatment was safe and effective, with a high rate of corneal restoration and improved vision for nearly all participants. The future of this therapy is bright, with researchers exploring ways to create an "off-the-shelf" version using stem cells from donor eyes, which could make the treatment available even to patients with damage in both eyes.

Gene Therapy: Correcting the Genetic Source of Dystrophy

While some therapies aim to replace damaged tissue, gene therapy offers a more fundamental solution: correcting the genetic errors that cause the disease in the first place. For Fuchs’ dystrophy, this approach is particularly promising, as researchers are now developing treatments using CRISPR gene editing to directly target the root cause of the disease.

Targeting the Faulty Gene

Most cases of Fuchs’ dystrophy are linked to an unstable genetic "stutter" in a gene called TCF4. The CRISPR-Cas9 system, often described as "molecular scissors," can be programmed to find this specific faulty DNA sequence within the corneal cells. Once located, it can make a precise cut to remove the toxic genetic material, allowing the cell to function normally again. The ultimate goal is to halt the death of endothelial cells and preserve the cornea’s natural pump function before vision is lost.

From the Lab to the Clinic

This research is rapidly moving from theory to practice. Pre-clinical studies have successfully demonstrated that this gene-editing technique can work in lab-grown human corneal cells and in animal models. The next step involves delivering this therapy to a patient’s eye, likely through a simple, one-time injection into the front of the eye. While human trials are still on the horizon, gene therapy holds the potential to be a single treatment that could prevent or even reverse Fuchs’ dystrophy.

Bioengineering the Cornea: Building a Better Solution

Beyond replacing cells, another exciting frontier involves building new corneal parts from scratch, with the goal of one day eliminating the need for donor tissue altogether. This field combines advanced materials science with biology to restore sight.

Tissue-Engineered Implants

Researchers are developing corneal implants using biocompatible materials like collagen. These are not simple plastic discs but sophisticated scaffolds designed to mimic the cornea's natural, transparent structure. By seeding these scaffolds with a patient's own cells before transplantation, the implant can integrate seamlessly into the eye, promoting regeneration while lowering the risk of immune rejection. The goal is a durable, off-the-shelf cornea that restores sight without a long wait.

Therapeutic Molecules

Scientists are also harnessing tiny, bioactive molecules to boost the body's own healing processes. This has led to the development of therapeutic eye drops containing peptides or growth factors that can accelerate wound healing, reduce inflammation, and prevent the formation of vision-clouding scars after an injury or surgery. This non-invasive approach could work as a standalone treatment for some conditions or as a powerful therapy to improve the success of a transplant.

3D Bioprinting

Pushing the boundaries even further is the revolutionary technology of 3D bioprinting. This technique uses a special "bio-ink"—a gel-like substance containing living corneal cells—to print a new cornea, layer by precise layer. This method allows for the recreation of the cornea's intricate architecture with incredible accuracy. While still experimental, 3D bioprinting holds the promise of creating fully personalized, on-demand corneas that are a perfect biological match for the patient.