Congenital toxoplasmosis is a specific form of the parasitic disease that occurs when an unborn fetus is infected with Toxoplasma gondii through the placenta. This transmission happens when a woman gets her first exposure to the parasite while she is pregnant, as she has not yet developed the immunity to protect her developing baby. The consequences can be severe, ranging from miscarriage and fetal death to a variety of serious health problems for the infant after birth. The timing of the maternal infection during pregnancy is a critical factor, with earlier infections generally leading to more severe outcomes for the child, making awareness and prevention crucial for expectant mothers.

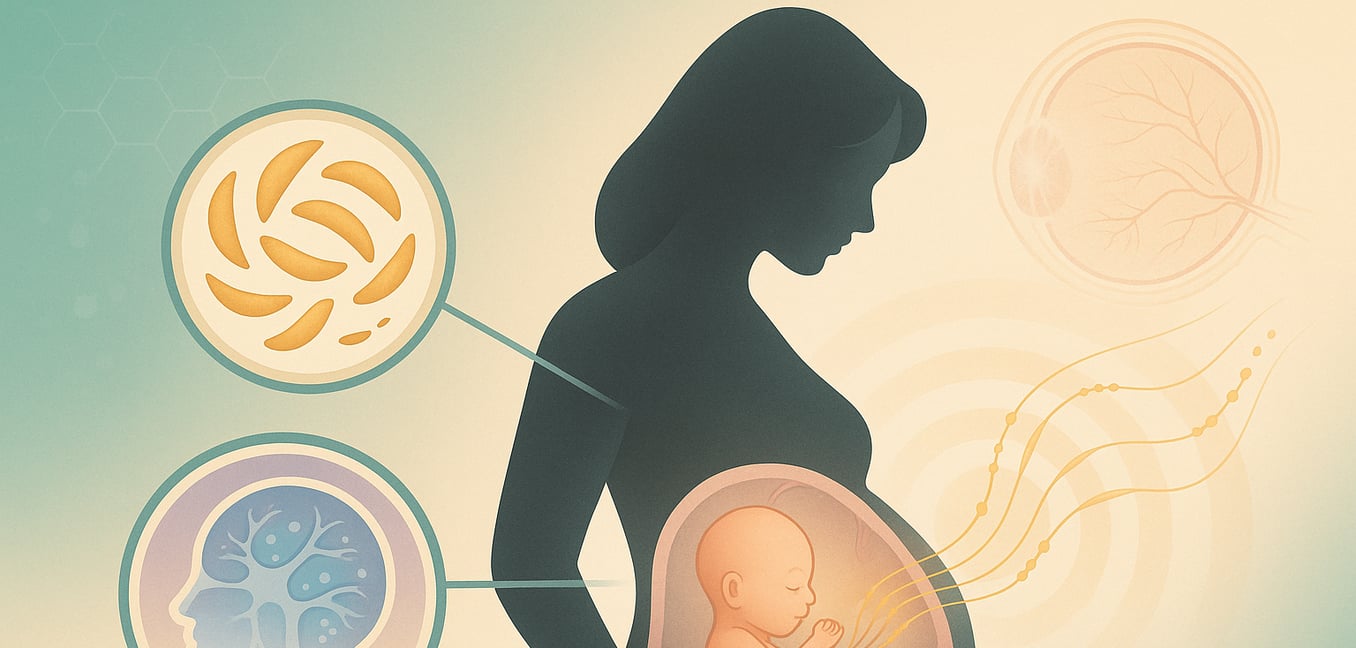

The most severe cases of congenital toxoplasmosis can present with a "classic triad" of symptoms, which includes chorioretinitis, hydrocephalus, and intracranial calcifications. Chorioretinitis is a severe inflammation of the retina and choroid layers of the eye, which can cause scarring and lead to vision impairment or blindness. Hydrocephalus, sometimes called "water on the brain," is a buildup of cerebrospinal fluid within the brain's ventricles, causing pressure that can lead to an enlarged head, brain damage, and developmental issues. Intracranial calcifications are small deposits of calcium in the brain tissue, indicating areas of prior damage from the infection. In addition to this triad, newborns may suffer from other immediate problems such as seizures, an abnormally small head (microcephaly), liver and spleen enlargement, low platelet counts, and skin lesions that can look like a "blueberry muffin" rash.

A significant challenge with congenital toxoplasmosis is that most infected infants show no obvious symptoms at birth but can develop serious health issues later in life, sometimes months or even years after. Ocular toxoplasmosis is a common delayed complication, where chorioretinitis can appear or recur, leading to progressive vision loss. Sensorineural hearing loss is another major risk, affecting a child's ability to hear and potentially leading to delays in communication and language skills. Furthermore, the neurological damage caused by the parasite can result in long-term consequences such as intellectual disabilities, learning disorders, poor coordination, and a persistent seizure disorder. The risk and severity of these outcomes underscore the importance of prenatal screening in some regions and prompt postnatal treatment for infected infants to mitigate long-term damage.

Can congenital toxoplasmosis be cured?

While there is no definitive cure that completely eradicates the Toxoplasma gondii parasite from the body, congenital toxoplasmosis is treatable. Treatment, which can last for a year or more, involves anti-parasitic medications that target the active, reproducing parasites to prevent further damage to the baby's brain, eyes, and other organs. However, these medications cannot eliminate the dormant cysts the parasite forms in the body's tissues. Because these cysts can reactivate later in life, infants born with the condition may still develop long-term complications, such as vision problems or developmental delays, and require lifelong monitoring.

How rare is congenital toxoplasmosis?

The rarity of congenital toxoplasmosis varies significantly depending on geographic location, public health policies, and local risk factors. Globally, the estimated incidence is about 1.5 cases for every 1,000 live births, but this figure masks major regional differences. The condition is far more common in South America, some Middle Eastern countries, and certain low-income nations, where incidence can be as high as 23 cases per 10,000 live births. In contrast, it is considerably rarer in many developed countries due to screening programs and public health education. For example, incidence rates are approximately 2.9 per 10,000 live births in France and fall between 0.5 and 1.0 per 10,000 in the United States, making it an uncommon diagnosis in these areas.

What are the long-term effects of congenital toxoplasmosis?

Congenital toxoplasmosis can lead to severe and lasting complications, which may not be apparent at birth and can develop later in childhood or even into adulthood. The most significant long-term effects are ophthalmologic and neurologic, with children being at risk for visual impairments from chorioretinitis, retinal scarring, and nystagmus. Neurologically, long-term sequelae include neurodevelopmental retardation, which can be severe, along with the later onset of seizures and the development of conditions like microcephaly. Furthermore, hearing loss can also emerge during the follow-up period, even in children who passed their initial newborn hearing screenings, highlighting the need for continuous, long-term monitoring for children diagnosed with the infection.

What are the three stages of toxoplasmosis?

The parasite that causes toxoplasmosis, Toxoplasma gondii , exists in three distinct infectious stages. The first is the tachyzoite, a rapidly multiplying form responsible for the initial, or acute, phase of the illness and any resulting tissue damage as it spreads throughout the body. As the immune system responds, the parasite transitions into the bradyzoite stage, a slow-dividing form that groups into tissue cysts, often in the brain and muscles, leading to a chronic, dormant infection that can reactivate later. The third stage is the sporozoite, which develops inside oocysts that are shed exclusively in the feces of cats; these oocysts become infectious after maturing in the environment and are a primary source of transmission when accidentally ingested.

How common is congenital toxoplasmosis in the US?

Determining the precise frequency of congenital toxoplasmosis in the United States is difficult because it is not a nationally notifiable disease, and no comprehensive national surveillance data exists. Although toxoplasmosis is reportable in eight states, significant variations in case definitions and reporting capacity make it challenging to generate reliable national estimates. The true incidence is likely underdiagnosed, as most infants with congenital toxoplasmosis appear normal at birth and may not develop symptoms until later in life. While studies estimate that about 11% of the U.S. population over age six has been exposed to the parasite, the specific number of babies born with the infection each year remains unknown due to these diagnostic and surveillance limitations.

What is the prognosis for congenital toxoplasmosis?

The long-term outlook for a child with congenital toxoplasmosis largely depends on the timing of diagnosis and the initiation of treatment. When detected and treated early with antiparasitic medications, typically for the first year of life, the prognosis is significantly improved, and many severe complications can be prevented or lessened. However, if the infection is severe at birth or if treatment is delayed, there is a higher risk of lasting health problems. These potential long-term effects can include vision damage from chorioretinitis (retinal inflammation), hearing loss, hydrocephalus (fluid buildup in the brain), seizures, and neurodevelopmental delays. For this reason, consistent, long-term follow-up care is essential to monitor for and manage any issues that may arise as the child grows.

What are the neurological symptoms of toxoplasmosis?

In individuals with weakened immune systems, a reactivated Toxoplasma gondii infection can cause severe neurological symptoms affecting the brain and spinal cord, including headaches, confusion, seizures, facial paralysis, and loss of motor skills. For babies born with the infection (congenital toxoplasmosis), symptoms may involve seizures, fluid on the brain (hydrocephalus), developmental delays, and learning differences. While most people with healthy immune systems do not experience symptoms, studies have explored links between chronic (latent) toxoplasmosis and various neurobehavioral disorders. Research suggests potential associations between the parasite and conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), epilepsy, and even suicide attempts, although a direct causal relationship has not been firmly established.