Diagnosing Marfan Syndrome: A Guide to the Process

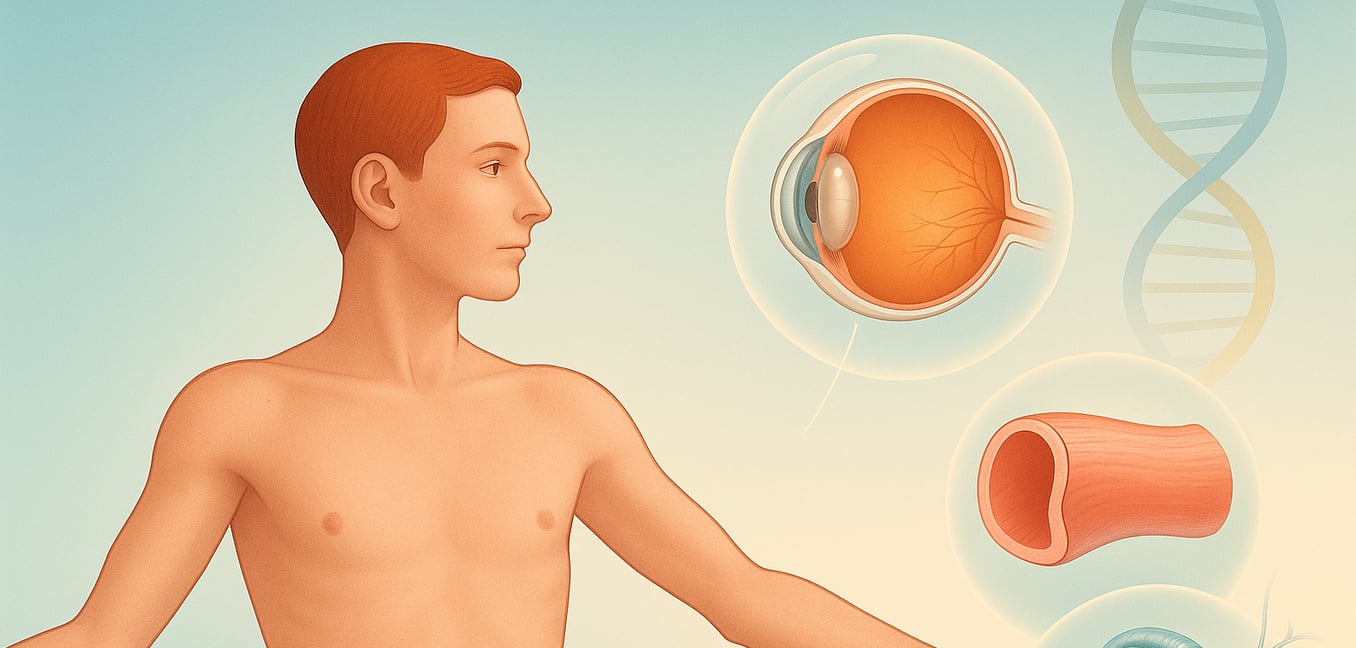

Marfan syndrome is a genetic disorder that affects the body's connective tissue. This tissue acts as the "glue" and scaffolding for the body, providing strength and support to structures like your skin, bones, heart, and blood vessels. Because connective tissue is found everywhere, Marfan syndrome can cause a wide range of signs that vary greatly from person to person.

The effects are most often seen in the skeleton, heart, and eyes. Understanding these key features is the first step in the diagnostic journey.

Key Signs and Symptoms

The diagnosis of Marfan syndrome relies on identifying a specific pattern of features across multiple body systems. While some signs are visible, others can only be detected through medical imaging and specialized exams.

Skeletal Features

The impact on the skeleton is often the most visible aspect of the condition.

- A characteristically tall, slender build with an arm span that is longer than the person's height.

- Unusually long, thin fingers and toes, a feature known as arachnodactyly.

- A chest wall deformity, where the breastbone either sinks inward (pectus excavatum) or pushes outward (pectus carinatum).

- Abnormal curvature of the spine, such as a side-to-side curve (scoliosis) or a forward hunch (kyphosis).

- Highly flexible joints (hypermobility), flat feet, and a long, narrow face with a high-arched palate and crowded teeth.

Cardiovascular Complications

These are the most serious health concerns associated with Marfan syndrome and require lifelong monitoring.

- Weakness in the wall of the aorta, the main artery carrying blood from the heart. This can cause the aorta to stretch and bulge (aortic aneurysm).

- A high risk of the aorta tearing, known as an aortic dissection, which is a life-threatening medical emergency.

- Problems with the heart's valves, particularly the mitral valve, which can become "floppy" and leak, a condition called mitral valve prolapse.

Eye and Vision Problems

The eyes are another area commonly affected by the disorder’s impact on connective tissue.

- Dislocation of one or both of the eye's lenses, a condition called ectopia lentis. This is a hallmark sign of Marfan syndrome.

- Severe nearsightedness (myopia) that often begins in early childhood.

- An increased risk for developing other eye conditions early in life, including cataracts, glaucoma, and retinal detachment.

The Clinical Evaluation: Piecing Together the Clues

The path to diagnosing Marfan syndrome begins with a thorough conversation and physical assessment. A doctor will start by gathering detailed personal and family medical histories, as these initial clues are crucial for guiding the diagnostic process.

Your Personal and Family History

A doctor will ask about your health and any symptoms you may be experiencing. This includes questions about vision problems, heart palpitations, shortness of breath, joint pain, or back pain. A detailed family history is one of the most powerful tools, as Marfan syndrome is often inherited. Be prepared to discuss if any relatives have been diagnosed with the condition or had features like being unusually tall and thin. It is also critical to mention any family members who experienced a sudden, premature death from a heart condition, especially an aortic aneurysm or dissection.

The Physical Examination

A hands-on physical exam is performed to look for the characteristic signs of the syndrome. A doctor will:

- Assess the skeleton: This includes measuring height and arm span to check their ratio and performing simple tests like the wrist and thumb signs to check for long fingers. The spine will be examined for scoliosis, and the chest for any deformities.

- Listen to the heart: Using a stethoscope, a doctor will listen for a heart murmur or a "click" sound, which can indicate problems like mitral valve prolapse or issues with the aorta.

- Examine the skin: The doctor will look for stretch marks (striae) that are not related to weight change or pregnancy, particularly on the back, shoulders, and abdomen.

- Check facial and oral features: The exam includes looking for a long, narrow face, deep-set eyes, and a high-arched, narrow palate inside the mouth.

Applying Formal Diagnostic Criteria: The Ghent Nosology

After the initial evaluation, a doctor uses a formal set of guidelines called the revised Ghent nosology to make a diagnosis. This system assigns points to different clinical findings, with the most weight given to aortic enlargement and lens dislocation. The final diagnosis depends on specific combinations of these features.

- Without a family history: A diagnosis can be made if a patient has an enlarged aorta and a dislocated eye lens. Alternatively, an enlarged aorta combined with a confirmed FBN1 gene mutation is also diagnostic.

- Using the systemic score: If a patient has an enlarged aorta but no lens dislocation, a point-based "systemic score" is used. Points are awarded for features like a positive wrist/thumb sign, scoliosis, chest deformity, and skin stretch marks. A score of 7 or more points is needed for diagnosis.

- With a family history: The diagnostic criteria are less strict for someone with a first-degree relative (parent, sibling, child) with Marfan syndrome. In this case, a diagnosis can be made with just one key feature, such as a dislocated lens, an enlarged aorta, or a systemic score of 7 or more.

Confirming the Diagnosis with Genetic Testing

While a diagnosis is often made based on clinical signs, genetic testing can provide a definitive answer by identifying the underlying mutation in the FBN1 gene, which provides the instructions for making a key connective tissue protein.

- Identifying the FBN1 mutation: A genetic test, usually done on a blood sample, can find a disease-causing error in the FBN1 gene. This confirms the diagnosis on a molecular level and explains the root cause of the patient's symptoms.

- Clarifying uncertain diagnoses: When symptoms overlap with other connective tissue disorders, genetic testing can pinpoint the exact condition. This is crucial for ensuring the correct treatment and monitoring plan is put in place.

- Guiding family screening: Once a specific mutation is found in a person, their relatives can be tested for that same mutation. This allows family members who have the condition but no symptoms to begin preventative care early and reassures those who did not inherit the gene.