What is the metabolic disorder known as GA1?

Glutaric Acidemia Type I (GA1) is an inherited metabolic disorder that prevents the body from correctly processing certain proteins. It belongs to a group of conditions called organic acid disorders. These disorders cause a harmful buildup of specific acids, known as organic acids. If not managed, this accumulation can be toxic to various tissues and organs, leading to serious health problems.

Understanding the Basics of GA1

GA1's core issues stem from a specific enzyme malfunction and its consequences:

- The Faulty Enzyme: The root cause of GA1 is a deficiency or malfunction of an enzyme called glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase (GCDH). This enzyme is a key worker in one of the body's chemical processing lines (a metabolic pathway) responsible for breaking down three amino acids: lysine, hydroxylysine, and tryptophan. These amino acids are essential building blocks of proteins we get from food. The GCDH gene provides the instructions for making this enzyme. If this gene has mutations (changes), the enzyme may not be produced in sufficient amounts or may not work correctly.

- Toxic Buildup: When the GCDH enzyme doesn't function properly, the body cannot effectively process lysine, hydroxylysine, and tryptophan. This leads to an accumulation of these amino acids and their intermediate breakdown products, such as glutaric acid and 3-hydroxyglutaric acid. When these substances reach high levels in the blood, urine, and tissues, they become toxic. The brain, especially regions called the basal ganglia which are crucial for controlling movement, is highly vulnerable to this toxicity.

- Varied Symptoms and Triggers: Symptoms of GA1 vary widely; some individuals have mild or no symptoms for years, while others face severe health issues. Often, initial signs appear in infancy or early childhood. These can be triggered by metabolic stress, such as infections, fever, or fasting, which can provoke an encephalopathic crisis (a period of acute brain dysfunction). A smaller number of individuals may not show clear signs until adolescence or adulthood, making diagnosis challenging without newborn screening.

- Physical Indicators and Risks: Babies with GA1 frequently, though not always, present with macrocephaly (an unusually large head circumference), which can be an early sign. If an encephalopathic crisis occurs, individuals may develop movement disorders like dystonia (involuntary muscle contractions causing twisting movements) or chorea (jerky movements), muscle rigidity, or hypotonia (low muscle tone). Importantly, some individuals with GA1 have developed bleeding in the brain (subdural hematomas) or eyes (retinal hemorrhages). Without a GA1 diagnosis, these findings could be tragically mistaken for signs of child abuse.

The Genetic Roots of GA1

GA1 is not contagious; it is a genetic condition passed down through families. It follows an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern.

The genetic basis of GA1 involves:

- The GCDH Gene: As mentioned, GA1 is caused by a faulty glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase enzyme. The GCDH gene, located on chromosome 19, provides the instructions for making this enzyme. Mutations in this gene disrupt its function.

- Inheritance Pattern: For a child to have GA1, they must inherit two mutated (non-working) copies of the GCDH gene – one from each parent.

- Carriers: Individuals who inherit one mutated GCDH gene copy and one working copy are called carriers. Carriers typically show no signs of GA1 because their single working gene produces enough functional enzyme. However, they can pass the mutated gene to their children.

-

Risk in Offspring:

When both parents are carriers, each pregnancy has:

- A 25% (1 in 4) chance the child will have GA1 (inheriting two mutated copies).

- A 50% (1 in 2) chance the child will be a carrier (inheriting one mutated and one working copy).

- A 25% (1 in 4) chance the child will not have GA1 and will not be a carrier (inheriting two working copies).

- Family History and Counseling: Many families have no known history of GA1 until a child is diagnosed, often via newborn screening. Genetic counseling is vital for affected families to understand inheritance, assess risks for future pregnancies, and discuss testing for other family members.

Biochemical Disruption: How GA1 Affects the Body

The genetic fault in GA1 sets off a chain reaction of harmful biochemical events, primarily impacting the brain and neurological function.

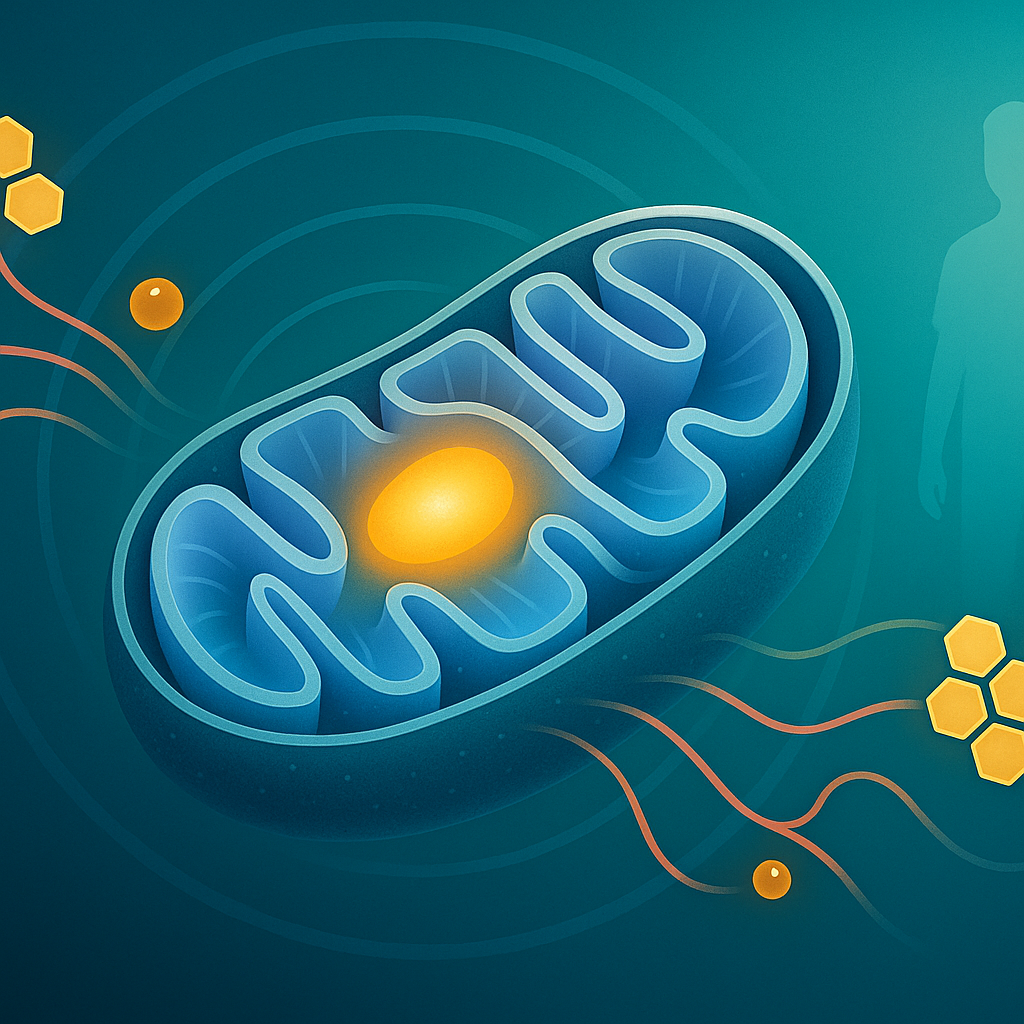

1. Toxic Metabolite Accumulation When lysine, hydroxylysine, and tryptophan are not properly processed, their byproducts – glutaric acid, 3-hydroxyglutaric acid, glutaryl-CoA, and glutaconic acid – build up. These substances are neurotoxic (harmful to nerve cells), particularly affecting the basal ganglia. This damage can occur when nerve cells become overexcited and "burn out" (excitotoxicity), or when harmful molecules build up causing damage to cells, similar to how rust damages metal (oxidative stress). These toxins can also interfere with mitochondria, the energy factories within cells, leading to movement problems and potential learning difficulties.

2. Secondary Carnitine Depletion The body attempts to remove these excess organic acids by attaching them to a molecule called carnitine, forming compounds like glutarylcarnitine, which are easier to excrete in urine. However, the high levels of organic acids in GA1 can overwhelm this system, depleting the body's carnitine stores. Carnitine is crucial for energy production, helping transport fats into mitochondria to be used as fuel. Low carnitine levels can impair energy generation, leading to muscle weakness and increased vulnerability during illness, which is why carnitine supplementation is often a treatment component.

3. Interference with Brain Signaling The chemical structures of accumulated metabolites like glutaric acid and 3-hydroxyglutaric acid resemble the brain's natural chemical messengers (neurotransmitters). These "rogue" metabolites can disrupt the brain's communication network. For instance, they may interfere with the glutamatergic system (involved in exciting nerve cells) and the GABAergic system (typically calming or inhibitory). Such disruptions can contribute to neurological symptoms like seizures and abnormal movements.

4. Exacerbation During Metabolic Stress The body's biochemical balance in GA1 can worsen dangerously under stress from infections (especially with fever), surgery, or fasting. During such times, the body naturally increases protein breakdown (catabolism) for energy. In GA1, this releases more lysine and tryptophan, leading to a rapid surge in toxic metabolite production. This can overwhelm the brain, often triggering an encephalopathic crisis – a sudden onset or worsening of severe neurological symptoms like seizures, extreme lethargy, and loss of motor skills – which can cause irreversible brain damage.

Recognizing GA1: Symptoms and Onset

Identifying GA1 can be challenging as symptoms vary and may not appear immediately. Newborn screening has improved early detection, but understanding symptom patterns is crucial.

1. Early Indicators One of the earliest potential clues, sometimes noticeable at birth or within the first few months, is macrocephaly (an unusually large head). Other subtle signs might include persistent poor feeding, unexplained irritability, or abnormal muscle tone, ranging from floppiness (hypotonia) to stiffness (rigidity). These can be mistaken for common infant issues.

2. Acute Encephalopathic Crises Many children with GA1, especially if not diagnosed through newborn screening, experience a dramatic acute encephalopathic crisis, typically between three months and three years of age. These are often triggered by metabolic stressors (illness, fasting). Symptoms include extreme lethargy, intense irritability, seizures, loss of developmental skills, and significant movement problems (dystonia, rigidity). Such crises can cause rapid, often permanent damage to the basal ganglia.

3. Insidious Onset and Developmental Delays Some individuals show a more gradual onset of symptoms. This might present as developmental delays, where a child misses motor milestones (rolling, sitting, crawling, walking) at expected times. Ongoing feeding difficulties leading to poor growth, or fluctuating muscle tone not linked to acute illness, can also occur. Abnormal movements like dystonia may develop slowly without a distinct crisis.

Diagnosis, Management, and Outlook

Early diagnosis and consistent management are key to a positive outlook for individuals with GA1.

Diagnosis

- Newborn Screening: The diagnostic journey often starts with a newborn blood spot test (heel prick) that screens for high levels of acylcarnitine (specifically C5-DC).

-

Confirmatory Tests:

If screening is abnormal, further tests include:

- Urine tests: To measure levels of glutaric acid and 3-hydroxyglutaric acid.

- Blood tests: To check for glutarylcarnitine.

-

Additional Tests:

In some cases:

- Enzyme activity tests: Assessing glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase activity in skin cells.

- Genetic testing: To identify mutations in the GCDH gene for a definitive diagnosis.

Management A specialized metabolic team oversees a multi-faceted approach:

- Dietary Plan: Strict limitation of lysine and tryptophan intake by restricting natural protein. Special lysine-free, tryptophan-low medical formulas ensure adequate nutrition for growth.

- L-Carnitine Supplementation: This medication helps the body excrete harmful glutaric acid and replenishes depleted carnitine stores.

- Emergency Management Protocol: Crucial during illness, fever, or stress. This involves increased calorie intake (often with high-glucose drinks or specialized emergency feeds) and temporarily stopping or significantly reducing protein to prevent a metabolic crisis.

Outlook With early diagnosis (especially via newborn screening) and lifelong adherence to treatment, the long-term outlook for individuals with GA1 has significantly improved. Many children can avoid severe brain damage and lead healthy lives with normal cognitive development. Regular follow-up appointments are essential to monitor growth, adjust diet, and check biochemical markers. While the risk of severe neurological crises decreases after about age six, continued vigilance with the emergency protocol and carnitine supplementation is usually recommended for life to ensure the best possible outcomes.