What Is Neuroblastoma?

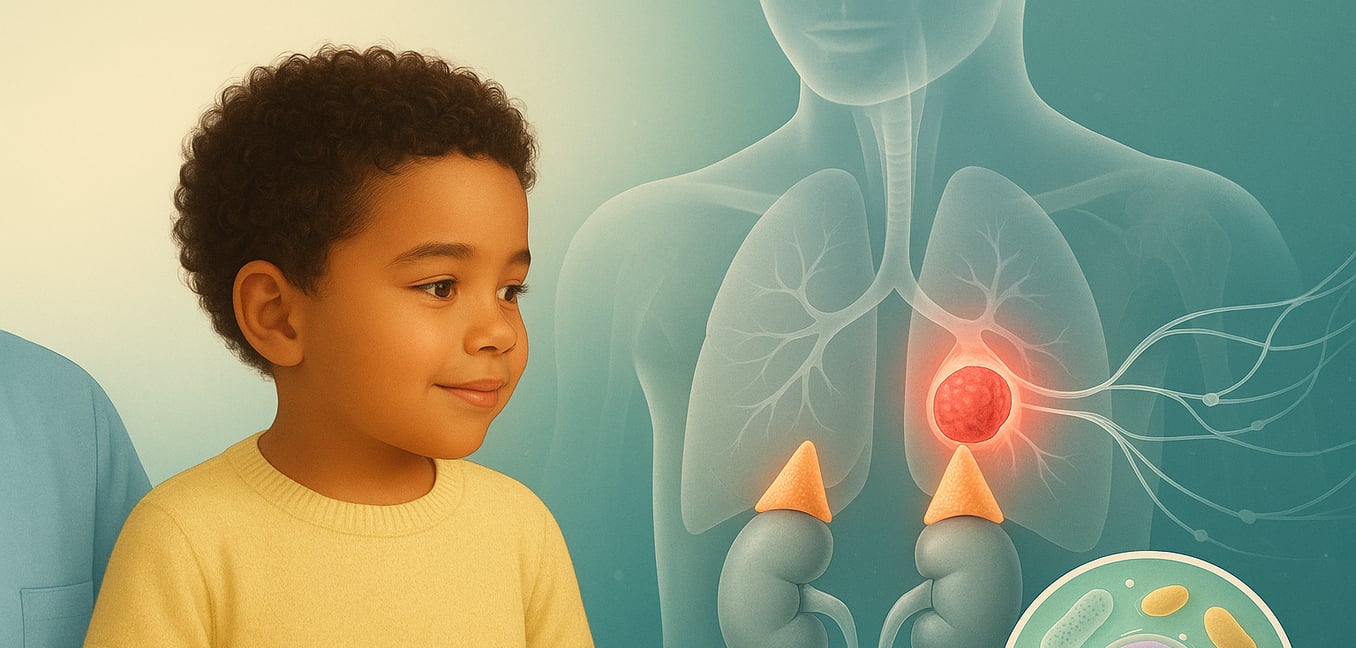

Neuroblastoma is a solid tumor cancer that arises from immature nerve cells called neuroblasts. These are the same cells that form the sympathetic nervous system in a developing fetus—the network that controls automatic functions like heart rate and blood pressure. The name reflects its origin: "neuro" for nerves and "blastoma" for a cancer of developing cells.

Primarily a cancer of infants and young children, neuroblastoma can form anywhere along the spine where this nerve tissue exists. The most common site is in the adrenal glands, which sit on top of the kidneys. Its behavior is notoriously unpredictable. In some infants, a tumor may disappear on its own or mature into benign tissue without any treatment. In older children, however, the disease is often aggressive, growing and spreading quickly to other parts of the body.

In over 98% of cases, neuroblastoma is sporadic, meaning it occurs from a random error during fetal development and is not inherited. It is not caused by anything a parent did or did not do, nor is it linked to any known environmental factors.

Recognizing the Signs and Symptoms

Because neuroblastoma can develop in many different locations, its symptoms are diverse and can often mimic common childhood illnesses, making diagnosis challenging. The signs a child shows depend on the tumor's size, its location, and whether the cancer has spread.

Abdominal Lumps and Swelling

A hard, painless lump in the abdomen is one of the most frequent signs, as many tumors start in the adrenal glands. This can cause a swollen belly, a poor appetite, or complaints of feeling full. The pressure from a tumor can also lead to constipation or unexplained weight loss, which can be easily mistaken for typical digestive problems.

Symptoms of Widespread Disease

When neuroblastoma spreads (metastasizes), it often travels to the bones and bone marrow. This can cause bone pain, particularly at night, or a limp without an obvious injury. Children may also become unusually irritable, tired, or pale from anemia (a low red blood cell count). A distinctive sign of widespread neuroblastoma is the appearance of dark, bruise-like circles around the eyes, often called “raccoon eyes,” caused by cancer spreading to the bones near the eye sockets.

Location-Specific Signs

The tumor's location can produce unique symptoms. A tumor in the chest may press on the windpipe, causing wheezing or breathing difficulties. A visible lump in the neck can sometimes interfere with nerves, leading to a drooping eyelid or a smaller pupil in one eye. In rare instances, neuroblastoma can trigger a neurological condition called opsoclonus-myoclonus-ataxia syndrome (OMAS), characterized by rapid, uncontrolled eye movements, jerky muscle spasms, and poor coordination.

The Diagnostic Process

If neuroblastoma is suspected, doctors will perform a series of tests to confirm the diagnosis, determine the tumor's characteristics, and see if it has spread. This step-by-step evaluation is essential for planning the right treatment.

The diagnostic workup usually includes:

- Imaging Tests: Doctors use ultrasound, CT (computed tomography), and MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scans to get detailed pictures of the tumor. These images show its exact size and location and reveal if it is pressing on vital organs or blood vessels.

- Urine and Blood Tests: These tests check for high levels of chemicals called catecholamines (specifically HVA and VMA) that are released by neuroblastoma cells and passed in the urine. Blood tests are also done to check for anemia and assess overall organ function.

- Biopsy: A surgeon removes a small piece of the tumor tissue, which is then examined under a microscope by a pathologist to confirm that it is neuroblastoma. A bone marrow aspiration and biopsy (taking a sample from the hip bone) is also standard to check if the cancer has spread there.

- MIBG Scan: This specialized imaging test is unique to neuroblastoma. A substance called MIBG, which is absorbed by most neuroblastoma cells, is attached to a small amount of radioactive iodine and injected into the body. A special camera then scans the body to create a map showing the primary tumor and any other areas where the cancer has spread.

Understanding Staging and Risk Groups

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, doctors determine the cancer's stage and assign a risk group. Staging maps out where the cancer is located in the body, while risk grouping predicts its likely behavior. Together, these classifications are the most important factors in deciding the type and intensity of treatment.

Determining the Stage

Doctors determine the stage by using imaging scans to see if the tumor has spread or is touching vital body parts like major blood vessels or the spinal cord. A localized tumor that has not spread and can be safely removed is considered a lower stage. If cancer cells are found in distant parts of the body, such as the bones, liver, or distant lymph nodes, the disease is classified as metastatic (Stage M), which is the most advanced stage.

Analyzing Tumor Biology

The biopsy sample provides crucial clues about the tumor’s "personality." Pathologists study the tumor's genetics and how the cells look under a microscope (histology). One of the most critical biological markers is the MYCN gene. If there are too many copies of this gene (a state called amplification), it acts like a gas pedal for cancer growth, indicating a more aggressive disease. Other chromosome changes are also analyzed to determine if the tumor has "favorable" or "unfavorable" biology.

Assigning a Risk Group

Finally, all the information—the child's age, the cancer's stage, and its biological features—is combined to place the child into a low, intermediate, or high-risk group. This classification directly guides the treatment plan. Low-risk patients may only need surgery or even just careful observation. Intermediate-risk patients typically receive chemotherapy and surgery. High-risk neuroblastoma requires a much more intensive, multi-stage treatment approach.

An Overview of Treatment Options

The treatment for neuroblastoma is tailored to each child's specific risk group. The goal is to cure the cancer while minimizing long-term side effects by matching the intensity of the therapy to the aggressiveness of the disease.

Surgery

For localized tumors, an operation to remove the cancerous mass may be the only treatment needed. The surgeon aims to remove as much of the tumor as possible without harming nearby organs. In higher-risk cases, chemotherapy is often given first to shrink the tumor, making it safer and easier to remove completely.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy uses powerful drugs that circulate through the bloodstream to kill cancer cells throughout the body. It is a cornerstone of treatment for intermediate and high-risk neuroblastoma, as well as for cancer that has already spread. The drugs are given in cycles, with treatment periods followed by rest periods to allow the body to recover.

Radiation Therapy

This treatment uses high-energy beams, like X-rays, to destroy cancer cells. For high-risk neuroblastoma, radiation is often used on the site of the original tumor after surgery to prevent it from growing back. It can also be used to treat painful spots where cancer has spread to the bones. A specialized form, MIBG therapy, delivers radiation directly to neuroblastoma cells throughout the body.

Advanced Therapies for High-Risk Disease

Treating high-risk neuroblastoma is a long and intensive process. It often involves high-dose chemotherapy followed by a stem cell transplant. This process destroys any remaining cancer cells but also wipes out the bone marrow, which is then replaced with the child’s own healthy stem cells that were collected earlier. After the transplant, patients receive immunotherapy, a treatment that activates the body’s own immune system to find and destroy any lingering cancer cells, which helps lower the chance of the cancer returning.