What is Glutaric Aciduria Type 1?

Glutaric Aciduria Type I (GA-I) is an inherited metabolic disorder. In this condition, the body cannot properly break down certain amino acids—protein building blocks—specifically lysine, hydroxylysine, and tryptophan. GA-I is passed down through families in an autosomal recessive pattern, meaning a child must inherit two copies of the faulty gene, one from each parent, to have the disorder. It is classified as a neurological condition and a type of organic aciduria, a group of metabolic disorders that primarily impact brain function due to the accumulation of acidic substances.

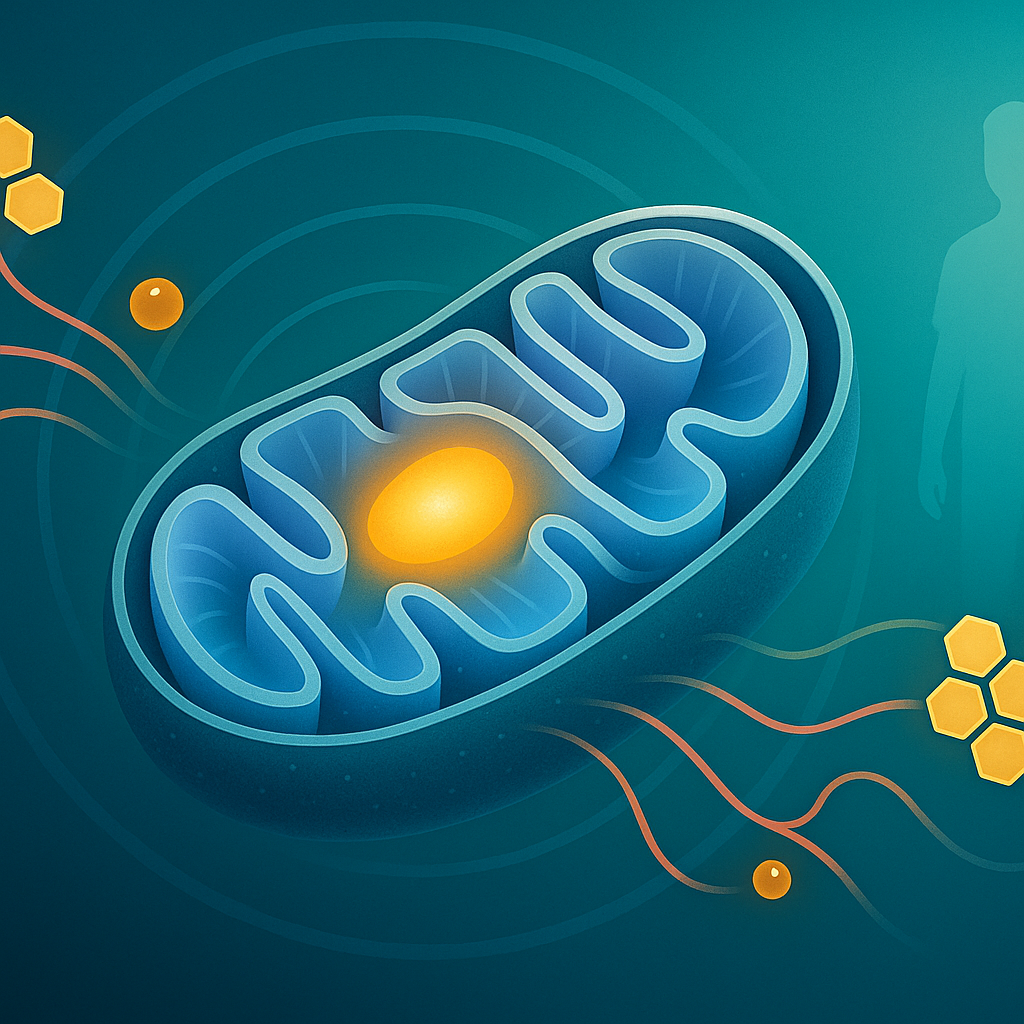

Underlying Cause: Enzyme Deficiency

The core issue in GA-I is a deficiency of an enzyme called glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase (GCDH). This enzyme is crucial for processing lysine, hydroxylysine, and tryptophan within the mitochondria, our cells' energy centers. When the GCDH enzyme is absent or not working correctly, these amino acids are not fully metabolized. The GCDH gene, located on chromosome 19, holds the instructions for producing this enzyme. Mutations in this gene are the genetic basis of GA-I.

Impact: Buildup of Harmful Substances

Due to the faulty GCDH enzyme, intermediate products of lysine, hydroxylysine, and tryptophan metabolism—specifically glutaric acid (GA), 3-hydroxyglutaric acid (3-OH-GA), and glutarylcarnitine (C5DC)—accumulate in the body's tissues and fluids, including blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid. Elevated levels of 3-OH-GA in urine and C5DC in dried blood spots are key biochemical markers for diagnosing GA-I, often detected through newborn screening. This buildup, especially of 3-OH-GA, is believed to be neurotoxic. It particularly damages the striatum, a part of the brain vital for coordinating movement, leading to the neurological problems characteristic of GA-I.

Common Signs and Symptoms

Many infants with GA-I appear healthy at birth but can develop symptoms later, often triggered by metabolic stress such as illness, fever, or fasting. Macrocephaly, an unusually large head size, is an early sign in about 75% of affected infants. Without early diagnosis and management, individuals may suffer acute encephalopathic crises—episodes of sudden brain dysfunction—typically between 6 and 18 months of age. These crises can cause lasting neurological damage, including dystonia (involuntary muscle contractions), seizures, developmental delays, and motor skill problems. However, severity varies; some individuals may have milder symptoms or remain asymptomatic into adulthood if the condition is managed effectively from an early age.

Early Indicators and the Role of Newborn Screening

Recognizing GA-I as early as possible is critical for a child's future, as prompt intervention can significantly improve the outcome of this serious condition. Newborn screening programs have revolutionized early diagnosis for many metabolic disorders, including GA-I, often identifying infants before any symptoms appear.

Newborn screening is a cornerstone of early GA-I detection. A small blood sample, usually from a heel prick, is analyzed using a sophisticated laboratory technique called tandem mass spectrometry to measure specific substances, most notably elevated levels of glutarylcarnitine (C5DC). This test, typically performed within the first few days of life, allows for the identification of affected infants before they become symptomatic or experience a potentially devastating encephalopathic crisis. Such early identification is vital because treatment aimed at reducing the buildup of harmful substances is most effective when initiated before neurological damage occurs, dramatically improving long-term outcomes.

It is important to understand that a positive newborn screen for GA-I is not a definitive diagnosis but an indication that further, more specific tests are needed immediately. These confirmatory tests usually involve analyzing urine for characteristic organic acids like 3-OH-GA and sometimes measuring GCDH enzyme activity in skin cells grown in a lab or in white blood cells. If these tests confirm GA-I, a specialized medical team, including metabolic specialists and dietitians, will quickly develop a comprehensive management plan. This rapid response is crucial because the window to prevent severe neurological complications is often narrow, especially in the first few months of life.

While newborn screening is ideal for early detection, some subtle clinical indicators might be present even before a diagnosis, or in regions without comprehensive screening. As noted, macrocephaly (an unusually large head circumference) is a common finding in many infants with GA-I, often noticeable at birth or developing within the first few months. Other less specific early signs might include poor feeding, hypotonia (low muscle tone), or irritability. In the absence of screening, these signs, particularly macrocephaly, should prompt healthcare providers to consider metabolic disorders like GA-I.

Typical Age of Clinical Presentation Without Early Screening

When newborn screening is unavailable or fails to detect Glutaric Aciduria Type 1 (GA-I), the condition typically manifests through clinical symptoms during a critical window in early childhood. Without early intervention, the onset of symptoms can be dramatic and may occur after some neurological damage has already begun.

Without newborn screening, GA-I typically reveals itself clinically between 3 months and 3 years of age. A significant number of these children experience their first acute encephalopathic crisis, a sudden episode of brain dysfunction, between 6 and 18 months. These crises are frequently triggered by common childhood stressors such as infections (like a cold, flu, or gastroenteritis), fever, vaccinations, or prolonged periods of fasting due to illness and poor appetite. During such a crisis, a child might suddenly become lethargic, irritable, vomit, have difficulty feeding, or develop seizures. This can potentially lead to a coma and, critically, irreversible damage to specific parts of the brain, particularly the basal ganglia (which includes the striatum, crucial for movement control).

Even before a full-blown encephalopathic crisis, some infants might display more subtle, earlier signs that, in retrospect, point towards GA-I. Macrocephaly is often present from birth or develops within the first few months and is a key indicator. Other early symptoms can include hypotonia (low muscle tone or "floppiness"), poor head control, difficulties with feeding leading to poor weight gain, or a general developmental delay where the child is slow to reach milestones like sitting up or crawling. These earlier signs can be non-specific and easily attributed to other causes if GA-I is not specifically considered.

Following an encephalopathic crisis, or sometimes developing more gradually even without a distinct crisis, children often begin to exhibit characteristic movement disorders. These result directly from damage to the basal ganglia and can include dystonia (involuntary muscle contractions causing twisting, repetitive movements, or abnormal postures), choreoathetosis (a combination of jerky, irregular movements and slower, writhing movements), and spasticity (stiff, tight muscles). These neurological signs, if the initial trigger was not clearly identified as an encephalopathic crisis, can sometimes be misdiagnosed as conditions like athetoid cerebral palsy, delaying correct diagnosis and treatment.

There is a spectrum in how GA-I presents when not caught by early screening. While an acute encephalopathic crisis in infancy is common, some individuals might have a later onset of symptoms or a more slowly progressive neurological decline without a single, identifiable crisis. The severity can also vary considerably, influenced by factors like the specific genetic mutation and individual responses to metabolic stress. This variability makes it crucial for healthcare providers to consider GA-I in any child presenting with unexplained neurological deterioration, movement disorders, or developmental regression, particularly if macrocephaly is also present.

Timing of Acute Encephalopathic Crises

Acute encephalopathic crises are particularly concerning events in Glutaric Aciduria Type 1, often marking a point where significant neurological changes can occur. Understanding when these crises are most likely to happen allows for heightened awareness and proactive management during these vulnerable periods.

The highest likelihood for the first acute encephalopathic crisis typically spans from 6 to 18 months of age, though occurrences can range from 3 months up to 3 years. This period aligns with rapid brain development and increased exposure to common childhood illnesses as maternal immunity wanes. The metabolic stress from these factors can overwhelm the impaired enzyme system in GA-I, leading to the buildup of harmful substances that trigger brain injury.

These crises are usually precipitated by events that increase metabolic demand or cause a catabolic state (where the body breaks down its own tissues for energy), often striking during or shortly after such an event. Febrile illnesses like colds, gastroenteritis, or even reactions to vaccinations are frequent triggers, as is prolonged fasting due to poor appetite or vomiting. These stressors force the body to break down its own proteins, including lysine and tryptophan. Due to the GCDH enzyme deficiency, these then accumulate as toxic byproducts, making this period particularly dangerous.

Many infants with GA-I may appear healthy for the initial months, potentially leading to a delayed recognition of risk if not identified by newborn screening. This seemingly normal period often precedes the high-risk window for crises. While the most intense period of vulnerability is within the first three years of life, especially between 6 and 18 months, the frequency of acute encephalopathic crises significantly decreases after age three. They become very rare after age six, although ongoing metabolic management remains essential.

It is important to differentiate the timing of acute encephalopathic crises from a more insidious, gradual neurological decline that can also occur in GA-I. Acute crises are distinct episodes of rapid deterioration, often with clear triggers, and are most common in the early years. While some neurological damage might accumulate slowly, these acute events represent concentrated periods of severe injury to the striatum, underscoring why their prevention during the peak age window is critical.

Extended Risk Period and Later Onset Considerations

While the most intense period for acute encephalopathic crises in Glutaric Aciduria Type 1 significantly diminishes after early childhood, the disorder's implications and potential for issues extend beyond these initial high-risk years. The risk profile changes, and some individuals may even experience their first noticeable symptoms much later in life.

Even though dramatic, acute crises become rare after age six, the underlying metabolic vulnerability persists throughout life. Ongoing, careful management, particularly adherence to dietary controls (like a protein-controlled diet low in lysine), remains essential to prevent growth disturbances, malnutrition, or the insidious development of neurological issues. Without consistent management, individuals could still face risks, emphasizing that the "risk period" involves maintaining long-term metabolic stability and neurological health.

Less commonly, GA-I can have a late onset, with individuals first showing clinical issues during adolescence or adulthood after being asymptomatic or having mild, unrecognized childhood symptoms. These later presentations vary, sometimes triggered by significant metabolic stress or manifesting as progressive neurological problems or movement disorders. Diagnosing GA-I in older individuals can be challenging if it is not immediately suspected past the typical crisis age, highlighting the need for awareness among healthcare providers.

Beyond acute crises and distinct late-onset forms, some individuals experience "insidious-onset GA-I." In these cases, striatal injury and neurological damage might occur very early, possibly even before or shortly after birth, or develop gradually without an obvious crisis. The resulting disability, such as motor delays or subtle movement problems, may only become apparent or correctly attributed to GA-I after several months or years. This scenario highlights an "extended risk period" not for new damage occurring later, but for the recognition of existing damage, where symptoms develop slowly and might be initially misattributed.