Neuroblastoma: A Cancer of Contrasts

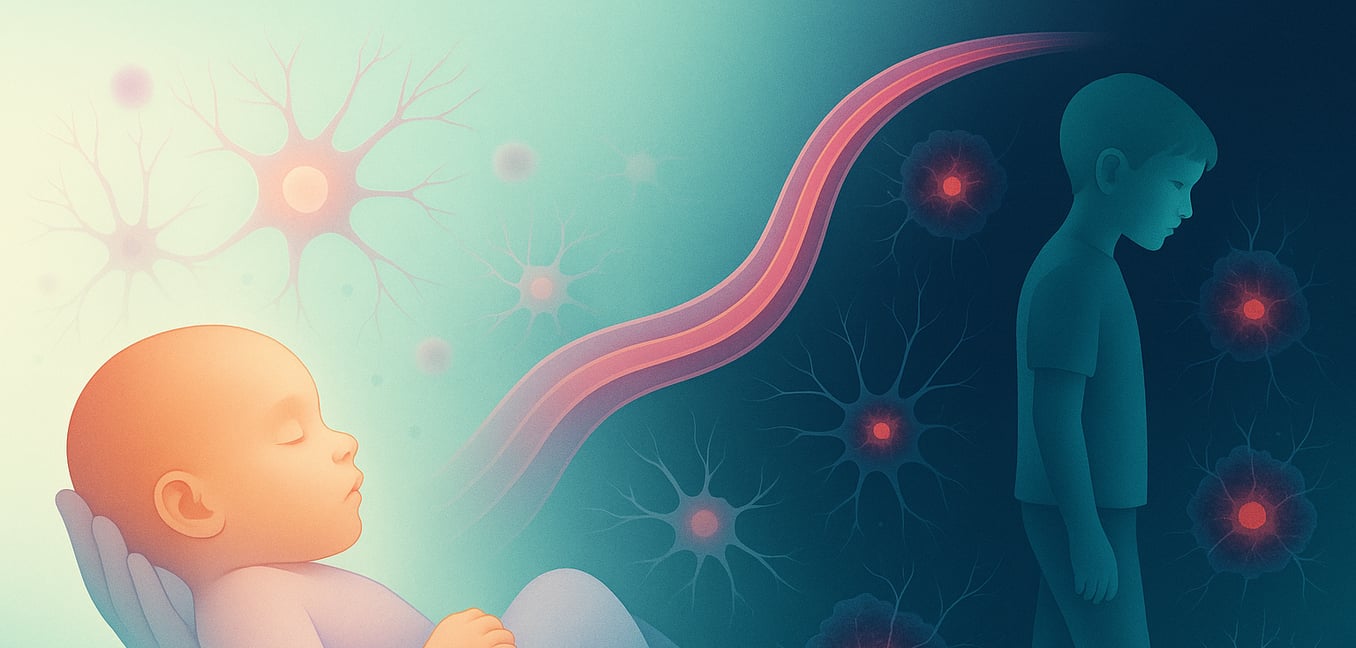

Neuroblastoma is the most common solid cancerous tumor in young children, originating from immature nerve cells called neuroblasts. These are leftover cells from a baby’s development that, instead of maturing into the sympathetic nervous system, grow out of control to form a tumor. Because of this developmental origin, the disease is most common in infants and toddlers.

While it is a single disease, neuroblastoma is defined by its remarkable variation. Its behavior can range from tumors that vanish on their own to an aggressive cancer that spreads relentlessly. A child's age at diagnosis is the single most important factor determining its path, creating a stark divide at around 18 months of age that dictates everything from prognosis to treatment. A tumor's genetic makeup is also critical, with markers like MYCN gene amplification signaling a more aggressive course, while mutations in the ALK gene can drive cancer growth and are sometimes responsible for the rare cases where the disease runs in families.

The Favorable Outlook in Infants (Under 18 Months)

For children diagnosed before 18 months of age, neuroblastoma often follows a much less aggressive path. These tumors typically have more favorable biological features, and many infants, even those with widespread disease, have an excellent prognosis. This hopeful outlook is largely due to the unique ability of these tumors to self-destruct.

Spontaneous Regression: A Disappearing Act

One of the most astonishing features of infant neuroblastoma is spontaneous regression, where a cancerous tumor shrinks and disappears without aggressive treatment. This phenomenon is almost exclusively seen in infants. A special stage of the disease known as Stage 4S, seen only in babies under one year old, is the classic example. In these cases, the cancer may have spread to the liver, skin, or bone marrow, yet the tumors often resolve on their own with little more than careful observation.

The Biology Behind Regression

Scientists believe several biological processes unique to infancy contribute to this remarkable outcome:

-

Loss of Growth Signals: Infant tumors often depend on a "growth signal" molecule that is abundant before birth but naturally fades afterward. Without this essential signal, the cancer cells effectively starve and undergo programmed cell death, causing the tumor to shrink on its own.

-

Natural Cellular Aging: Many infant tumors lack the enzyme needed to rebuild the protective caps on their chromosomes, called telomeres. With each cell division, these caps shorten until they reach a critical point, triggering the cells to stop dividing and die. This built-in clock effectively prevents the tumor from growing indefinitely.

-

A Robust Immune Response: Evidence suggests that an infant's developing immune system can recognize and attack neuroblastoma cells. This is supported by rare cases where a child's immune system strongly attacks both the tumor and parts of the nervous system. While this causes neurological symptoms, it is linked to a much better cancer prognosis, hinting that a powerful anti-tumor immune response can lead to regression.

The Aggressive Challenge in Older Children (Over 18 Months)

The clinical picture changes dramatically for children diagnosed after 18 months. These patients are far more likely to face an aggressive, advanced cancer that requires intensive treatment and carries a significant risk of returning.

High-Risk Genetics and Widespread Disease

Unlike the localized tumors often seen in infants, neuroblastoma in older children tends to spread to distant parts of the body, such as the bone marrow and bones, before it is even discovered. This advanced disease is driven by a fundamentally different set of genetic features.

The tumors in older children are far more likely to have the high-risk genetic alterations mentioned earlier, such as MYCN amplification, which acts like a gas pedal stuck to the floor, fueling rapid and relentless growth. They also frequently feature deletions of protective genetic material on chromosomes 1p and 11q. Together, these changes create a biologically aggressive cancer that is challenging to treat from the outset.

The Persistent Threat of Relapse

Perhaps the most daunting challenge for older children is the high probability that the cancer will return after treatment. Even when intensive therapies lead to a complete response where no cancer can be detected, the risk of recurrence remains substantial.

This age-based difference is starkly reflected in survival data. One major analysis found that the 5-year recurrence-free survival rate for children diagnosed under 18 months was over 74%. For those diagnosed at or over 18 months, that rate plummeted to just 37%. This means that while a majority of successfully treated infants remain cancer-free, fewer than four out of ten older children do.

Critically, age emerges as an independent risk factor in statistical models. Even after accounting for tumor stage and other biological markers, being 18 months or older at diagnosis makes a child more than three times as likely to relapse. This highlights that the neuroblastoma cells in older children possess a greater intrinsic resilience, allowing them to survive therapy and re-emerge later. It is not just that their cancer is harder to treat initially, but that it is fundamentally more prone to coming back.