Glutaric aciduria type 1 (GA1) is an uncommon inherited metabolic disorder. It affects how the body processes certain building blocks of protein called amino acids, specifically lysine, hydroxylysine, and tryptophan. This problem arises from a deficiency in an enzyme known as glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase (GCDH), which is caused by alterations in the GCDH gene.

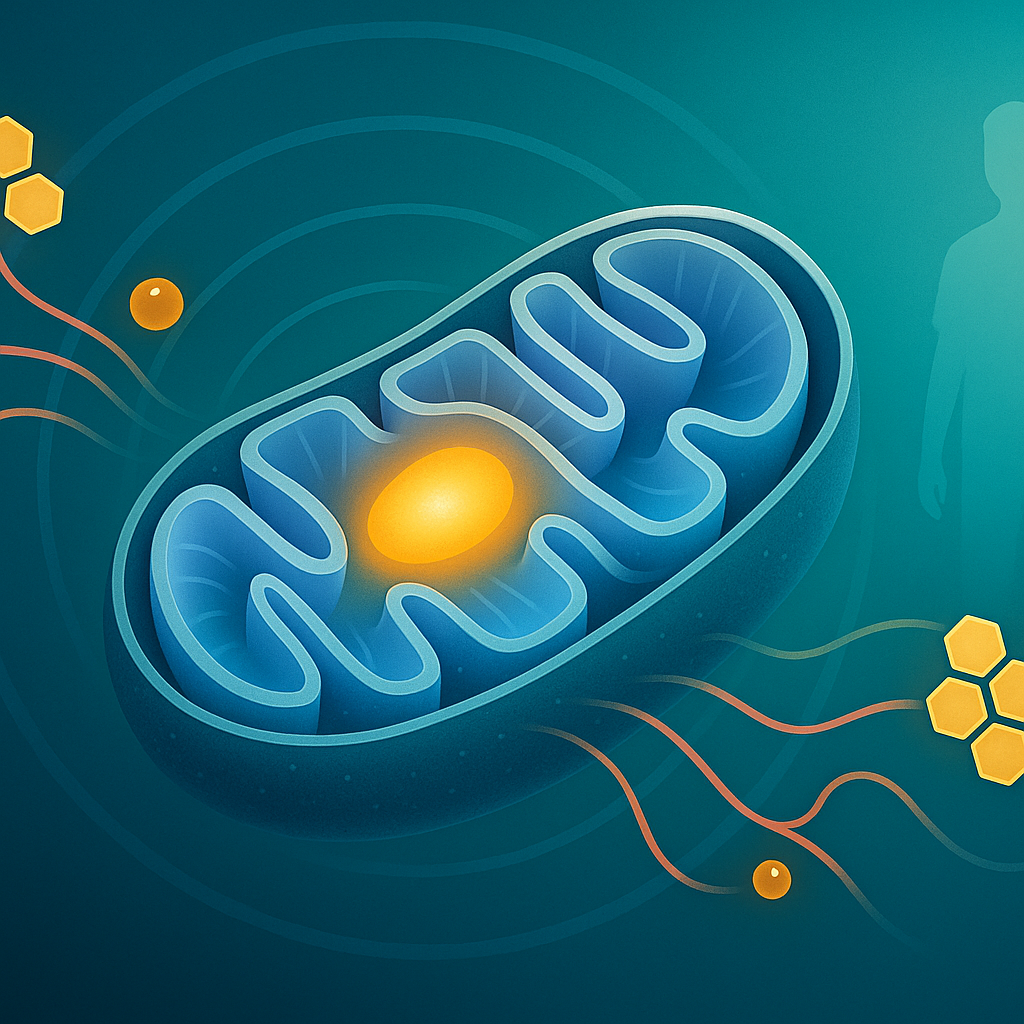

When the GCDH enzyme doesn't function correctly, these amino acids are not broken down completely. As a result, harmful substances (including glutaric acid and 3-hydroxyglutaric acid) accumulate in the body. These substances are neurotoxic, meaning they can damage brain cells and tissues, particularly in a brain region called the striatum, which plays a key role in controlling movement. This toxic buildup is the underlying cause of the various neurological symptoms associated with GA1.

Symptoms of GA1 often emerge within the first few years of life. A common trigger for the first severe symptoms is an illness (like a cold or stomach bug), vaccination, or surgery. These situations create bodily stress and cause tissues to break down (a state known as catabolic stress), leading to a rapid increase in the harmful substances. This can provoke a sudden and serious neurological decline called an 'encephalopathic crisis,' potentially resulting in permanent brain injury. However, GA1 doesn't always present this way; some individuals may experience a more gradual onset of symptoms without a clear crisis (insidious onset), or symptoms may not appear until after age six (late-onset GA1). An unusually large head (macrocephaly) can be an early physical sign. GA1 is an autosomal recessive condition, meaning a child develops it by inheriting two altered copies of the GCDH gene, one from each parent, who are usually unaffected carriers.

Early Indicators: Signs in Newborns and Infants

Identifying Glutaric Aciduria Type 1 early, ideally before a significant health crisis, is crucial for effective management. While many newborns with GA1 appear healthy, certain subtle signs may develop during infancy that can alert parents and healthcare professionals.

- Unusually Large Head (Macrocephaly) : Often the earliest and most noticeable physical sign, macrocephaly may be present at birth or develop within the first few months. The infant's head circumference might be in the upper percentile range or grow faster than typical. This enlargement can be linked to underlying brain changes, such as widened fluid spaces, characteristic of GA1, and unexplained macrocephaly warrants medical investigation for conditions like GA1.

- Decreased Muscle Tone (Hypotonia) : Infants with GA1 might exhibit low muscle tone, often described as feeling "floppy" or having reduced muscle strength. This can manifest as difficulty with head control or a general lack of resistance when their limbs are moved. Hypotonia can also affect feeding, as weaker muscles may impair sucking and swallowing abilities.

- Subdural or Retinal Hemorrhages : In some infants, GA1 can cause bleeding within the brain (subdural hemorrhage) or eyes (retinal hemorrhages), sometimes with minimal or no apparent trauma. These serious occurrences, typically within the first few years, can sometimes be mistaken for non-accidental injury. Such bleeding, especially if accompanied by other GA1 indicators like macrocephaly, requires urgent medical evaluation, including screening for metabolic disorders.

- Subtle Neurological or Behavioral Changes : Infants may display slight alterations in their neurological state or behavior. This could include persistent, unexplained irritability beyond normal fussiness, or unusual lethargy with excessive sleepiness and difficulty rousing for feeds. Some might show fine tremors or jittery movements not attributable to cold or being startled, potentially reflecting the brain's early sensitivity to metabolic disruption.

Neurological and Movement-Related Difficulties

The neurological problems in Glutaric Aciduria Type 1 primarily result from damage caused by the buildup of harmful substances, especially to the basal ganglia – brain structures critical for regulating movement. When these areas are affected, particularly following an encephalopathic crisis, various movement and coordination issues can arise, significantly impacting daily life.

The specific neurological and movement-related difficulties include:

- Dystonia : This is a common movement disorder in GA1, characterized by involuntary, sustained, or intermittent muscle contractions. These contractions often cause twisting, repetitive movements, or abnormal, sometimes painful, postures affecting limbs, the trunk, or facial muscles. Dystonia can interfere with voluntary actions like walking, writing, speaking, or swallowing, and its intensity may fluctuate, often worsening with stress or illness.

- Dyskinesia and Choreoathetosis : Uncontrolled, involuntary movements, collectively termed dyskinesia, are also frequent. This can present as chorea (rapid, jerky, unpredictable movements) or athetosis (slower, continuous, writhing motions). These movements can be highly disruptive, making it hard to sit still, perform coordinated tasks, or maintain a stable posture, with considerable variation among individuals.

- Other Motor Control Issues : Beyond dystonia and dyskinesia, individuals might experience muscle rigidity (stiffness and resistance to movement) or spasticity (increased muscle tone leading to stiffness and spasms). Some may also have ongoing low muscle tone (hypotonia) or muscle weakness. These contribute to difficulties with gross motor skills like sitting and walking, and fine motor skills like self-feeding.

- Variability in Severity and Cognitive Impact : The severity of these movement disorders varies greatly; some individuals are mildly affected, while others face severe, debilitating challenges. Although movement control centers are most prominently damaged, intellectual disability can occur, especially with widespread brain injury or recurrent crises. However, many individuals with GA1, particularly those diagnosed and treated early, can have normal cognitive development.

Understanding the Acute Encephalopathic Crisis

An acute encephalopathic crisis (AEC) is a sudden, severe neurological event that can occur in individuals with Glutaric Aciduria Type 1, particularly in young, undiagnosed children or those whose condition is not yet optimally managed. These crises are typically precipitated when the body is under stress, leading to increased tissue breakdown (catabolism) and a surge in the harmful metabolites characteristic of GA1. An AEC can cause profound and often permanent brain damage, especially to the striatum.

Key aspects of these crises include:

- Common Triggers : Everyday childhood illnesses causing fever, such as colds, flu, ear infections, or gastroenteritis, are frequent triggers. Vaccinations, though vital, can sometimes induce a feverish reaction that acts as a trigger. Surgical procedures or prolonged periods without food (fasting), perhaps before a medical test or due to illness-related appetite loss, can also push the body into a catabolic state, increasing crisis risk.

- Early Warning Signs : Recognizing the initial signs of an impending crisis is crucial for rapid intervention. A child might become unusually irritable or difficult to console. They may also show decreased appetite, refuse feeds, or experience vomiting or diarrhea. A noticeable increase in lethargy, with excessive sleepiness or difficulty waking, alongside worsening hypotonia, are key indicators of a developing crisis.

- Symptoms During a Full Crisis : Once an AEC fully develops, neurological symptoms can be dramatic, reflecting acute brain injury. Children may suddenly lose previously acquired developmental skills like babbling or sitting (developmental regression). There can be an abrupt onset or significant worsening of movement disorders like dystonia or dyskinesia. Seizures may occur, and in severe instances, a child might develop opisthotonus (severe muscle spasms causing rigid arching of the back) or even fall into a coma.

Other Notable Symptoms and Complications

Beyond the well-known movement disorders and the danger of acute crises, Glutaric Aciduria Type 1 can lead to several other symptoms and complications. These additional challenges can affect various aspects of health, development, and daily functioning, often requiring careful ongoing management.

- Secondary Carnitine Deficiency : GA1 often leads to a deficiency in carnitine, a substance the body uses to help remove excess glutaric acid. This depletion can impair energy production from fats, potentially worsening muscle weakness and fatigue. L-carnitine supplementation is therefore a standard part of treatment.

- Growth and Developmental Delays : The metabolic stress of GA1, combined with potential feeding difficulties, can sometimes hinder physical growth and overall development. Delays may extend beyond motor skills to affect speech, language, and social milestones, particularly if neurological damage has occurred. Early intervention therapies are vital.

- Cognitive and Learning Challenges : While cognitive outcomes differ, GA1 can pose risks for learning difficulties or intellectual disability, especially if encephalopathic crises cause significant brain injury. The impact can range from mild learning issues to more severe cognitive impairment. Consistent metabolic management is key to protecting brain health.

- Feeding Difficulties and Nutritional Concerns : Maintaining the necessary specialized low-lysine, low-tryptophan diet can be challenging due to feeding issues like poor appetite or oral-motor problems linked to hypotonia or dystonia. These difficulties can affect nutrient intake, sometimes requiring modified food textures or tube feeding.

- Progressive Brain Structural Changes : In addition to the characteristic basal ganglia damage from acute crises, some individuals may show other evolving brain abnormalities over time, such as atrophy (shrinkage) in the frontal and temporal lobes. These structural changes, visible on neuroimaging, can influence long-term neurological and cognitive outcomes.