A Guide to Surgical Options for Omphalocele

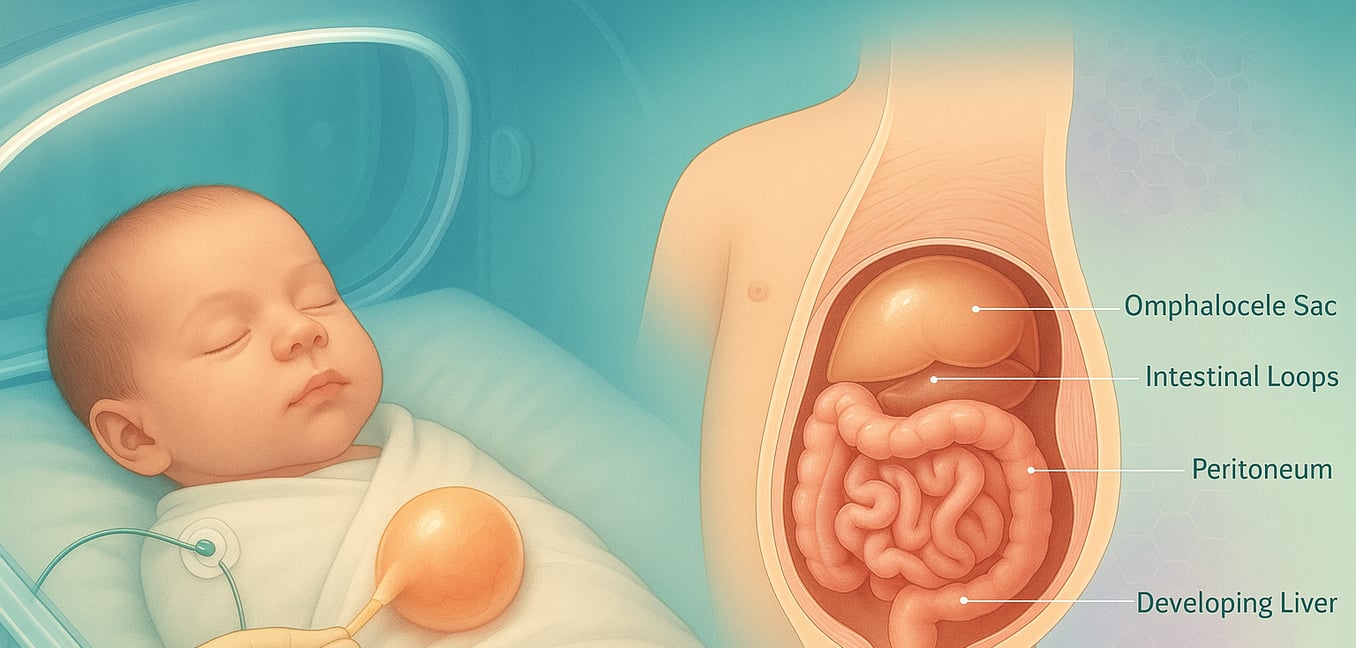

An omphalocele is a birth defect of the abdominal wall where an infant's intestines, and sometimes other organs like the liver, protrude through the navel. This occurs when the abdominal wall fails to close completely during fetal development, leaving the organs contained in a thin, protective sac. Once a baby with an omphalocele is born, immediate care in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is critical. The primary goals are to protect the exposed organs, maintain the baby's body temperature and hydration, and provide respiratory support before a surgical plan is determined.

The surgical strategy depends largely on the size of the omphalocele, the organs involved, and the baby's overall health. The main options are a single-stage primary repair for smaller defects or a multi-step staged repair for larger ones.

Surgical Option 1: Primary Repair

A primary repair is a single-stage surgical procedure to place the organs back into the abdomen and close the opening. This approach is typically performed within the first few days of life when the baby is stable and the defect is small enough for a safe, immediate closure.

Ideal Candidates for Primary Repair

This single-stage surgery is generally reserved for infants with smaller omphaloceles, where only a portion of the intestine is outside the body. A key factor is whether the baby's abdominal cavity is large enough to accommodate the organs without causing a dangerous increase in internal pressure, which could restrict breathing and blood flow. The newborn must also be medically stable, with no other severe health issues that would make a major operation too risky.

The Surgical Procedure

The procedure is performed while the baby is under general anesthesia. The surgeon begins by removing the protective sac that encloses the organs. After a careful examination for any other defects, the organs are gently placed back inside the abdominal cavity. Once everything is in its proper position, the surgeon closes the layers of the abdominal wall, including the muscle and skin, completing the repair in one comprehensive operation.

Post-Operative Care

Following surgery, the infant is monitored closely by the specialized NICU team. Some babies may need temporary support from a breathing machine as their body adjusts to the new pressure within the abdomen. A small tube, often placed through the nose into the stomach (a nasogastric tube), helps keep the stomach empty and allows the bowel to rest and heal. Feedings are introduced gradually as the baby's bowel function returns, starting through the tube and slowly transitioning to feeding by mouth.

Surgical Option 2: Staged Repair for Large Defects

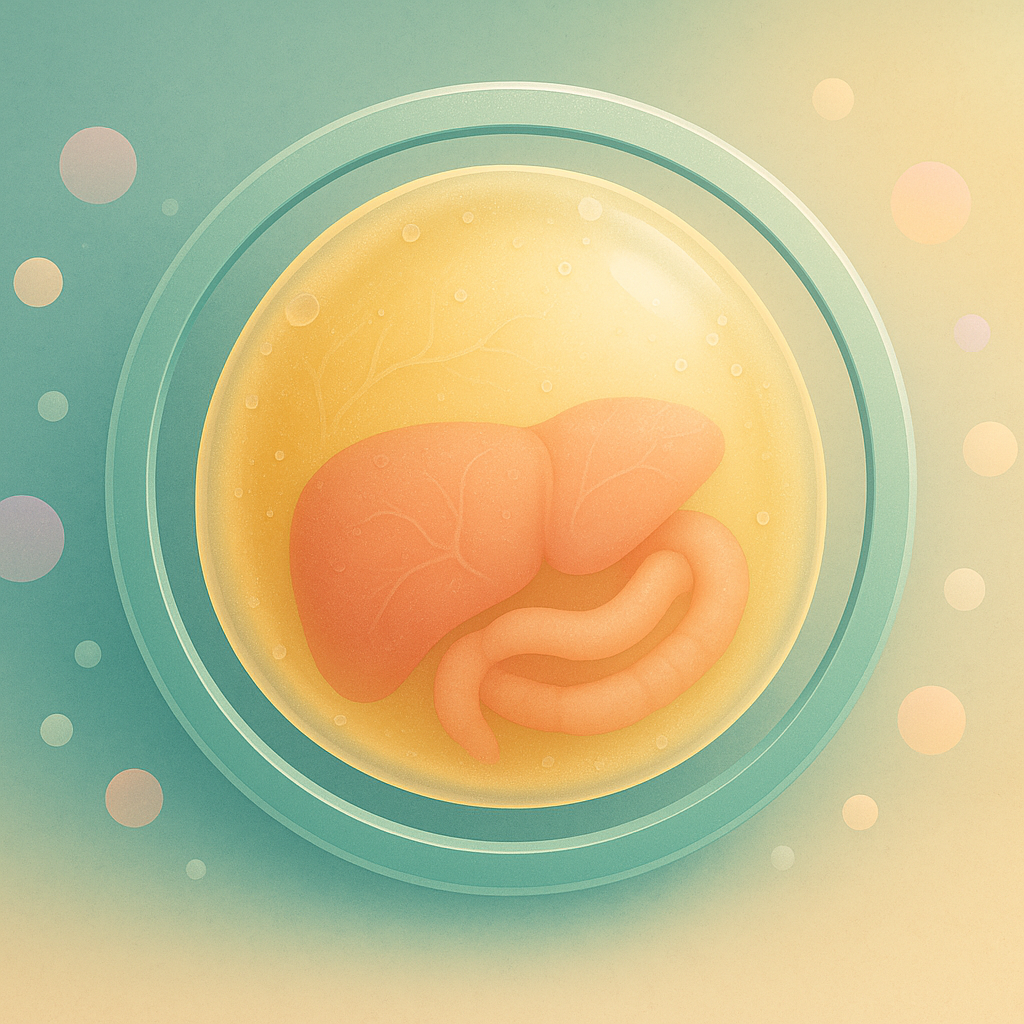

For babies born with a giant omphalocele, where a large portion of the abdominal organs, including the liver, are outside the body, a single-stage repair is often not possible. The abdominal cavity is too small to receive all the organs at once. In these cases, a staged repair provides a gradual, multi-step process to give the baby’s body time to adapt.

The Silo-Based Approach

A common first step involves placing a sterile, plastic pouch called a silo over the protruding organs. This silo is sutured to the edges of the abdominal wall defect, creating a safe, temporary enclosure. This protects the organs from infection and fluid loss while allowing the baby's condition to stabilize. Over several days or weeks, the clinical team gently squeezes and tightens the silo, slowly pushing the organs back into the abdominal cavity. This gradual reduction allows the abdomen to stretch and grow, avoiding a sudden, dangerous rise in internal pressure. Once all the organs are back inside, the baby undergoes a final surgery to remove the silo and close the abdominal wall.

The "Paint and Wait" Approach

In some cases, particularly for infants who are too medically fragile for any immediate surgery, a non-operative initial strategy called "paint and wait" is chosen. This patient technique uses the body's natural healing process as a bridge to a definitive surgical repair later in life. A topical antimicrobial cream is regularly applied to the omphalocele sac, which helps it to toughen and prevents infection. Over many months, the baby's own skin slowly grows inward from the edges, a process called epithelialization. This transforms the omphalocele into a large, stable, skin-covered hernia. This approach can often allow the baby to be cared for at home, with a final surgical repair planned for when the child is much older, bigger, and stronger.

Advanced Surgical Techniques for Giant Omphaloceles

Closing the final defect in a giant omphalocele presents significant challenges, requiring specialized planning and advanced surgical methods. The focus is not just on closure but on managing the associated health issues, particularly respiratory function.

Addressing Pulmonary Hypoplasia

A critical challenge with giant omphaloceles is managing the baby's underdeveloped lungs, a condition known as pulmonary hypoplasia. Because the organs developed outside the body, the abdominal cavity remained small, preventing the lungs from expanding fully. As a result, many of these infants require prolonged support from a mechanical ventilator. In some cases, a tracheostomy—a surgical opening in the windpipe—is necessary to provide a stable, long-term airway, giving the lungs crucial time to grow before the final abdominal closure is attempted.

Complex Abdominal Wall Closure

When it is time for the final repair, the gap in the abdominal wall is often too wide to be stitched together directly without creating excessive tension. To solve this, surgeons may use special materials to bridge the defect, such as a synthetic patch or a biologic mesh derived from donated tissue. These materials act as a scaffold, providing support while allowing the baby’s own tissues to grow over and incorporate the patch. In more complex cases, surgeons may use an advanced technique called "component separation." This involves surgically releasing layers of the abdominal wall muscles to allow them to be stretched toward the midline, helping to achieve a secure closure.

Life After Surgery: Long-Term Considerations

Even after a successful closure, children who were born with a giant omphalocele often require long-term follow-up care. Immediately after the final repair, they are monitored for abdominal compartment syndrome, a dangerous increase in internal pressure that can affect blood flow to vital organs.

Many children also experience significant feeding difficulties and gastroesophageal reflux (GERD), which may require specialized formulas, feeding tubes, or medication. Because the liver may be positioned higher in the abdomen after repair, it can be more vulnerable to injury, meaning contact sports are often discouraged later in childhood. Continued care from a team of specialists helps manage these challenges and supports the child's healthy development.