How Marfan Syndrome Diagnosis Differs in Children and Adults

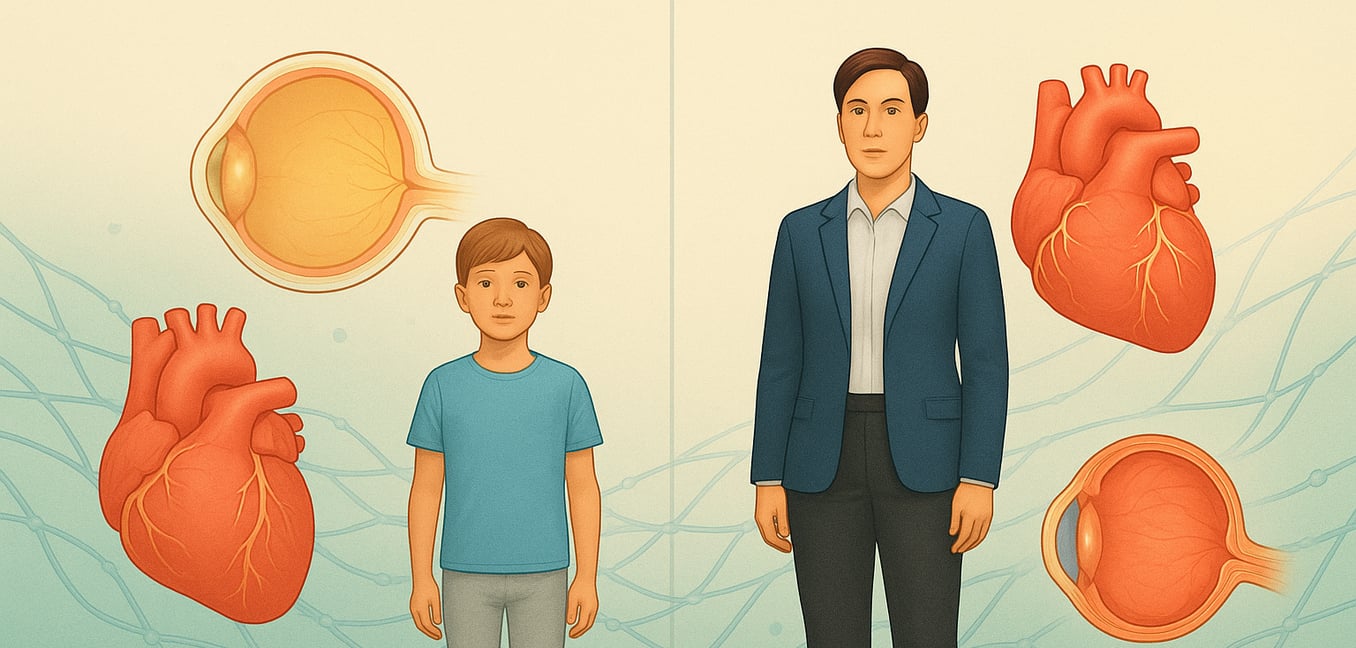

Marfan syndrome is an inherited disorder of the body's connective tissue, the "glue" that supports our organs, blood vessels, bones, and joints. It is caused by a defect in the FBN1 gene, which disrupts the production of a protein essential for tissue elasticity. While the underlying genetic cause is the same for all patients, the way the condition presents and is diagnosed can differ dramatically depending on a person's age.

Diagnosing Marfan Syndrome in Children: An Evolving Picture

In children, a diagnosis of Marfan syndrome often hinges on recognizing either a set of severe, obvious signs at birth or a more subtle collection of features that emerge and evolve throughout childhood.

The Severe Neonatal Presentation

A rare but severe form, often called neonatal Marfen syndrome, is apparent from birth. These infants require immediate medical attention, and the diagnosis is typically suspected based on a dramatic combination of signs that are hard to miss. Key indicators include:

- Striking physical signs: Infants may be born with unusually long limbs and fingers, joint contractures that limit movement, and a characteristic facial appearance with deep-set eyes and crumpled-looking ears.

- Severe heart and breathing issues: A prominent heart murmur caused by severe leakage of the mitral and tricuspid valves is a hallmark. This quickly leads to heart failure and can cause significant breathing difficulties.

- Failure to thrive: Feeding difficulties and poor weight gain are critical red flags. The effort of breathing and pumping blood is so taxing that these infants struggle to eat and grow, a condition known as "failure to thrive."

Diagnosis in Later Childhood

More commonly, the features of Marfan syndrome appear gradually as a child grows. The diagnostic process becomes a matter of tracking these developing signs over time, making regular check-ups essential. An initial suspicion may arise from a single feature, such as a child being exceptionally tall for their age or needing glasses for severe nearsightedness.

Clinicians look for an accumulating pattern of signs, including a disproportionately long arm span, a curved spine (scoliosis), or a chest wall deformity. Because features like aortic enlargement and systemic signs may not be present or fully developed yet, a definitive diagnosis can sometimes be delayed. This makes ongoing monitoring by a multi-specialty team crucial, as the clinical picture can change significantly during periods of rapid growth.

Diagnosing Marfan Syndrome in Adults: A Cumulative Puzzle

When Marfan syndrome is not identified in childhood, diagnosing it in an adult is like assembling a puzzle from pieces collected over a lifetime. The features may have developed so subtly over the years that the individual or their doctors never connected them. The diagnostic process is a methodical investigation that combines a thorough physical exam, a detailed personal and family history, and specialized imaging.

A key difference in the adult diagnosis is the importance of the patient's history. An adult can report things a child cannot, such as chronic back pain from dural ectasia (stretching of the spinal sac) or a history of a collapsed lung. The presence of stretch marks on the skin without significant weight changes provides another clue.

Furthermore, a detailed family history becomes a powerful tool. Learning that a parent, sibling, or other close relative had an aortic aneurysm, a sudden unexplained death, or a confirmed diagnosis of Marfan syndrome provides strong evidence and can significantly streamline the diagnostic process.

The Diagnostic Toolkit: Applying Formal Criteria and Genetic Testing

To ensure an accurate and consistent diagnosis, clinicians use a standardized set of guidelines called the Ghent nosology, alongside advanced imaging and genetic testing. The application and interpretation of these tools vary based on the patient's age.

The Ghent Criteria: A Standardized Framework

First established in 1996 and revised in 2010, the Ghent criteria provide a formal roadmap for diagnosis. They are built on several key pillars:

- Aortic Root Dilation: An enlargement of the aorta where it leaves the heart is a major criterion. In children, this measurement is complex; it must be compared to norms for their specific body size and converted into a "Z-score" to determine if it is disproportionately large for their growing body. In adults, the measurement is more straightforward.

- Ectopia Lentis: A dislocation of the eye's lens is a cardinal feature. If present, it is a powerful indicator of Marfan syndrome at any age and can secure the diagnosis on its own. Annual eye exams are recommended for at-risk children to check for this specific sign.

- A Systemic Score: When a dislocated lens is absent, diagnosis relies on combining aortic dilation with a high score on a systemic checklist. This system awards points for features like skeletal signs, skin stretch marks, and other characteristics, requiring a total of seven or more points. For children, achieving a high score can be difficult as some features, like certain chest deformities or dural ectasia, may not be apparent yet. This means a child might not meet the full criteria initially and may require re-evaluation as they get older.

Genetic Testing: A Tool for Confirmation

A blood test can identify a disease-causing mutation in the FBN1 gene, offering a definitive answer in many cases. However, its role and interpretation differ.

In a newborn with severe, life-threatening features, a genetic test can provide rapid confirmation and guide urgent medical decisions. For family members of a person with a known FBN1 mutation, testing can clearly determine if they also have the condition, avoiding a lifetime of unnecessary screening if the result is negative.

Crucially, a genetic test cannot predict the severity or progression of the disease. Two people with the same mutation can have vastly different health outcomes. Furthermore, in about 5-10% of individuals who meet the clinical criteria for Marfan syndrome, no mutation can be found with current technology. For this reason, a diagnosis still rests heavily on the comprehensive clinical evaluation, with genetic testing serving as a powerful but not infallible component of the assessment.