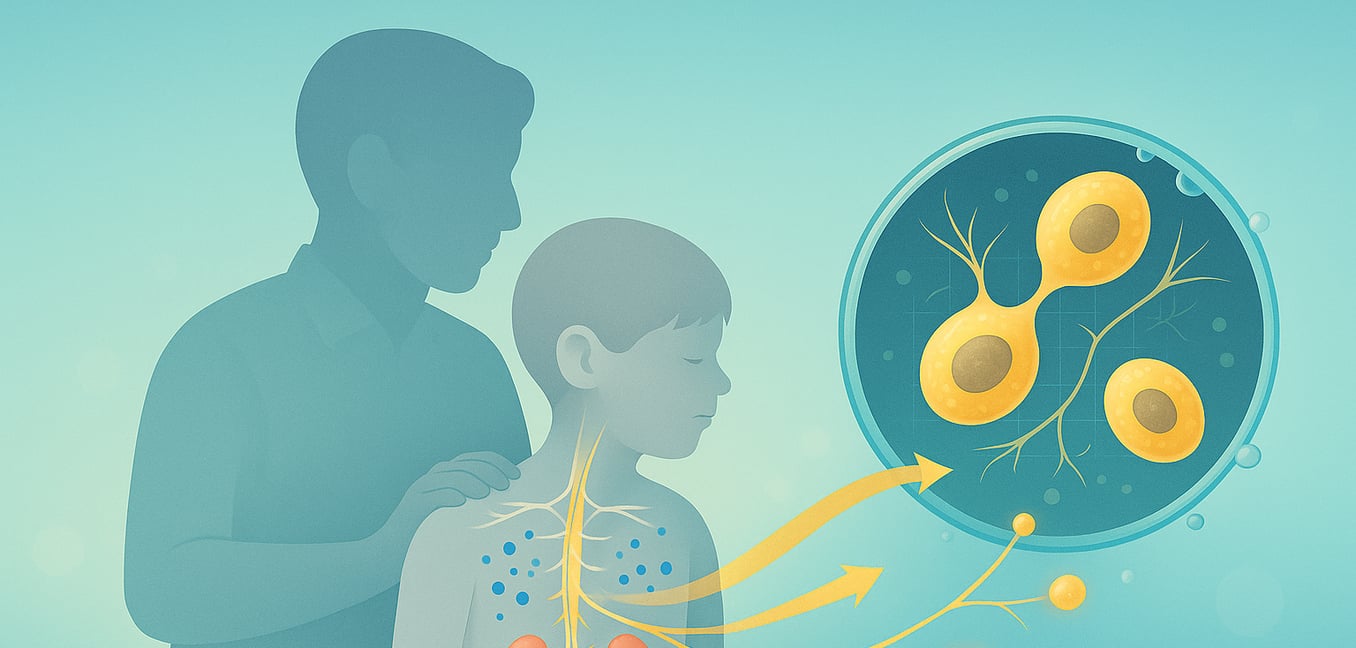

Understanding Neuroblastoma and How It Spreads

Neuroblastoma is a solid tumor cancer that arises from immature nerve cells called neuroblasts. It is one of the most common cancers in infants and young children, typically forming in the adrenal glands located on top of the kidneys or in nerve tissue along the spine in the neck, chest, or abdomen. While the exact cause involves a genetic mutation, a critical factor for treatment and prognosis is whether the cancer remains localized or spreads to other parts of the body—a process called metastasis. This article explores the typical pathways and destinations of neuroblastoma spread.

The Pathways and Destinations of Metastasis

When neuroblastoma metastasizes, cancer cells break away from the primary tumor and travel to new locations. This process can occur through several routes, each leading to common destinations. Understanding how and where the cancer travels is key to diagnosis and treatment planning.

Direct Invasion of Nearby Tissue

The most straightforward form of spread is local invasion. Like a plant's roots expanding in soil, the tumor can grow directly into adjacent tissues and organs. For example, a neuroblastoma that starts in an adrenal gland might grow large enough to press on or invade the nearby kidney. To ensure all cancerous cells are removed, surgeons often aim to remove the tumor along with a small margin of surrounding healthy tissue.

Travel Through the Lymph System

The lymphatic network, a key part of the immune system, can act as a highway for cancer cells. If cells break away and enter this system, they can be transported through lymph fluid and become trapped in lymph nodes—small, bean-shaped glands that filter the fluid. Once inside a lymph node, the cancer cells can multiply and form a new metastatic tumor, causing the node to swell. Doctors frequently check lymph nodes near the primary tumor to see if the cancer has begun to spread.

Travel Through the Bloodstream

The bloodstream provides the most extensive route for cancer to travel to distant parts of the body. Once in circulation, neuroblastoma cells tend to settle and grow in specific sites.

Bones and Bone Marrow

The skeletal system is the most frequent destination for metastatic neuroblastoma. When cancer settles in the bones, it can cause significant pain, which is often a primary symptom that leads to a diagnosis. If it invades the bone marrow—the spongy tissue inside bones that produces blood cells—it can disrupt the production of red cells, white cells, and platelets. This can lead to anemia, frequent infections, or easy bruising. To detect this type of spread, doctors rely on tests like bone scans and bone marrow biopsies.

Liver

The liver is another common destination, particularly in infants with a specific subtype of the disease. The presence of many small tumors can cause the liver to become significantly enlarged. This may make a baby’s abdomen appear swollen and can sometimes cause breathing difficulties if the enlarged organ presses up against the diaphragm. Imaging tests such as ultrasound, CT, or MRI are used to check for cancer in the liver.

Skin

In very young infants, neuroblastoma can spread to the skin, which is a less common but notable site of metastasis. This spread typically appears as small, firm, painless lumps that have a distinctive bluish or purplish color, sometimes mistaken for bruises. The presence of these skin nodules is a key diagnostic sign for a unique pattern of neuroblastoma seen only in infants.

How Age Influences the Pattern of Spread

The age of a child at diagnosis plays a remarkable role in determining where neuroblastoma is likely to metastasize. These age-specific patterns are so consistent that they help doctors define risk categories and tailor treatment strategies for each patient.

The Infant Pattern (Stage MS)

In infants younger than 18 months, a unique pattern of metastasis known as Stage MS (or 4S in older systems) can occur. In this scenario, the cancer spreads widely but specifically to the skin, liver, and a limited amount of bone marrow. Crucially, it typically spares the bones themselves. This pattern leads to visible signs like bluish skin lumps and a swollen abdomen from an enlarged liver. Despite being widespread, this form of neuroblastoma often has a very good prognosis and, in some cases, may even regress on its own with careful observation rather than aggressive treatment.

The Pattern in Older Children

For children diagnosed after 18 months of age, the metastatic journey is typically more aggressive. In this group, the cancer is far more likely to spread extensively to distant lymph nodes, the bones, and the bone marrow. Bone involvement is a hallmark of the disease in older children and is a common cause of the pain that brings them to medical attention. This invasive pattern means these children are almost always classified as high-risk and require intensive therapies.

The Pattern in Adolescents and Young Adults

Although neuroblastoma is rare in adolescents and young adults, its behavior can differ again when it does occur. While these older patients can experience spread to the bones and bone marrow, they also have a higher likelihood of metastasis to organs less commonly affected in younger children, such as the lungs and the brain. This variation presents unique clinical challenges and highlights why a single treatment approach is not effective for this complex disease.

Impact of Spread on Staging and Treatment

The presence of distant metastasis is one of the most significant factors in determining a child's prognosis and treatment plan. It signals that the cancer is a systemic disease that requires a body-wide approach.

Staging the Spread

When neuroblastoma spreads to distant parts of the body, it is assigned the highest stage. In the modern International Neuroblastoma Risk Group Staging System (INRGSS), this is called Stage M. In the older International Neuroblastoma Staging System (INSS), it is known as Stage 4. These classifications confirm that cancer cells have traveled through the blood or lymph system to establish new tumors in distant sites. The main exception is the unique Stage MS category for infants with spread limited to the skin, liver, and bone marrow.

Defining the Risk

A diagnosis of metastatic disease (Stage M or 4) almost always places a child in either the intermediate-risk or high-risk category. For any child over 18 months with distant spread, the classification is automatically high-risk, which requires the most intensive treatment protocols available. This risk level is also informed by other factors, including the tumor's genetic features, such as amplification of the MYCN gene, which makes the cancer more aggressive.

The Challenge of Recurrence

For children with high-risk, metastatic neuroblastoma, one of the greatest challenges is cancer recurrence. Even after intensive therapy appears to eliminate the disease, a few resilient cancer cells can survive and begin to grow again later. Recurrent neuroblastoma is often harder to treat, as the surviving cells may have developed resistance to the initial chemotherapy. Because of this, a major focus of ongoing research is to find new ways to target these persistent cells and prevent the cancer from returning.